Study Notes: Stanford CS336 Language Modeling from Scratch [15]

A hands-on guide to training a math reasoning model with GRPO on Lambda Cloud using 2xH100 GPUs — improving Qwen2.5-Math-1.5B accuracy from ~6% to ~25% with practical implementation details.

Training Math Reasoning Models with GRPO on Lambda Cloud with 2xH100s

We’ve all read about GRPO (Group Relative Policy Optimization) and have a rough grasp of the theory. But a practical question often remains: how do you actually train a math reasoning model with GRPO?

This post aims to bridge the gap between understanding GRPO on paper and running it on real cloud hardware.

Using Qwen2.5-Math-1.5B as a concrete example, I’ll walk through how to improve its math accuracy from ~6% to ~25%—a 4× improvement—by training with GRPO on Lambda Cloud using 2× H100 GPUs. Along the way, I’ll share:

How GRPO is implemented in practice

How to structure a 2-GPU training setup (policy model + vLLM inference)

How to read and reason about GRPO training curves and what signals actually matter

The goal is not just to explain what GRPO is, but to show how it behaves end-to-end in a real training run—from reward computation, to GPU allocation, to interpreting the final plots.

This guide builds on my previous study notes on reinforcement learning for language models. If terms like “policy gradient” or “advantage” are unfamiliar, start there first.

Table of Contents

- Training Math Reasoning Models with GRPO on Lambda Cloud with 2xH100s

- Table of Contents

- Notation

- Why GRPO for Math Reasoning?

- GRPO Intuition: Groups as Your Baseline

- GRPO vs PPO/RLHF

- The Algorithm Step-by-Step

- Key Implementation Details

- GRPO Experiment on Lambda Cloud Setup with 2×H100 (80GB SXM5)

- Interpreting Training Plots

- Evaluation Results: Base Model vs GRPO-Trained

- Summary and Key Takeaways

Notation

Before diving in, here’s a quick reference for the mathematical symbols used throughout this guide:

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| $\pi$ | Policy — the language model being trained |

| $\theta$ | Parameters — the model weights |

| $\pi_\theta(a \mid s)$ | Probability of generating token $a$ given context $s$, under model with weights $\theta$ |

| $G$ | Group size — number of responses sampled per question |

| $R$ | Reward function — scores each response (e.g., 1 if correct, 0 if wrong) |

| $r^{(i)}$ | Reward for the $i$-th response in a group |

| $V(s)$ | Value function — estimates expected future reward from state $s$ (used in PPO, not GRPO) |

| $A$ | Advantage — how much better a response is compared to baseline |

| $\mu_G$, $\sigma_G$ | Mean and standard deviation of rewards within a group |

| $\epsilon$ | Small constant (e.g., 1e-6) to prevent division by zero |

| $\rho$ | Importance sampling ratio — $\pi_\theta / \pi_{\theta_{old}}$, used for off-policy correction |

Don’t worry if these aren’t all clear yet — each will be explained in context as we go.

Why GRPO for Math Reasoning?

Large language models struggle with multi-step math reasoning. They might solve “2+3” but fail on “If a train leaves at 2pm traveling 60mph, and another train leaves at 3pm traveling 80mph…“—problems requiring chained logical steps.

GRPO offers a simpler alternative to full RLHF:

| Approach | Value Function? | Complexity | When to Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| RLHF with PPO | Yes (separate model) | High | When you need maximum performance |

| GRPO | No (group statistics) | Medium | When you want simplicity + good results |

| Vanilla REINFORCE | No | Low | When you’re learning/debugging |

Key insight: GRPO uses the diversity of multiple responses to the same question as a “natural” baseline, eliminating the need to train a separate value network.

The approach was introduced in DeepSeekMath and later refined in DeepSeek-R1.

GRPO Intuition: Groups as Your Baseline

The “Group” Concept

For each question, GRPO samples G different responses from the current model. These responses form a group. Instead of judging each answer in isolation, GRPO compares responses against each other.

If some responses are correct and others are wrong:

- The correct ones are better than the group average → they should be reinforced

- The incorrect ones are worse than the group average → they should be actively de-emphasized

In other words, GRPO does two things at once:

Pushes up good responses

Pushes down bad responses, without needing an explicit value baseline or a separate critic

By normalizing rewards within the group, GRPO naturally:

Encourages the model to repeat reasoning patterns that work

Discourages failure modes and bad reasoning trajectories

The group itself becomes the baseline: “Given multiple ways I could have answered this question, which ones should I do more often—and which ones should I avoid?”

This relative comparison is what makes GRPO both simple and stable, especially for domains like math reasoning where clear correctness signals exist.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Question: "What is 15 × 7?" │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────┐ │

│ │ Response 1 │ │ Response 2 │ │ Response 3 │ │ Response 4 │ │

│ │ "105" ✓ │ │ "105" ✓ │ │ "112" ✗ │ │ "107" ✗ │ │

│ │ reward = 1 │ │ reward = 1 │ │ reward = 0 │ │ reward = 0 │ │

│ └─────────────┘ └─────────────┘ └─────────────┘ └─────────────┘ │

│ │

│ Group mean = 0.5 Group std = 0.5 │

│ │

│ Advantages: │

│ A₁ = (1-0.5)/0.5 = +1.0 ← Reinforce! │

│ A₂ = (1-0.5)/0.5 = +1.0 ← Reinforce! │

│ A₃ = (0-0.5)/0.5 = -1.0 ← Discourage! │

│ A₄ = (0-0.5)/0.5 = -1.0 ← Discourage! │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Key insight: GRPO only learns from diversity. If all G responses were correct (or all wrong), the advantages would be zero and no learning would occur. This is why sampling temperature matters and we need some exploration!

GRPO vs PPO/RLHF

Here’s how GRPO compares to standard RLHF with PPO:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ RLHF with PPO │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ ┌──────────────┐ ┌──────────────┐ ┌──────────────┐ │

│ │ Policy Model │ │ Value Model │ │ Reward Model │ │

│ │ (train) │ │ (train) │ │ (frozen) │ │

│ └──────────────┘ └──────────────┘ └──────────────┘ │

│ │ │ │ │

│ ▼ ▼ ▼ │

│ Generate response Estimate expected Score response │

│ │ return V(s) │ │

│ │ │ │ │

│ └────────────────────┼──────────────────────┘ │

│ ▼ │

│ Advantage = R - V(s) │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ GRPO │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ ┌──────────────┐ ┌──────────────┐ │

│ │ Policy Model │ │ Reward Model │ │

│ │ (train) │ │ (frozen) │ │

│ └──────────────┘ └──────────────┘ │

│ │ │ │

│ ▼ ▼ │

│ Generate G responses Score all G │

│ for same question responses │

│ │ │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ ▼ │

│ Advantage = (R - mean) / std │

│ (computed from G siblings) │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

| Aspect | RLHF/PPO | GRPO |

|---|---|---|

| Value function | Trained separately | Not needed |

| Memory | 2 full models | 1 model + reward function |

| Baseline | Learned V(s) | Group statistics |

| Compute | Higher | Lower |

| Implementation | Complex | Simpler |

Why this matters: for a 1.5B-parameter model, GRPO saves roughly ~3 GB of VRAM by eliminating the need for a separate value network. This reduction is substantial—especially when running on consumer or constrained GPUs—and often makes the difference between fitting the model comfortably and needing aggressive memory hacks.

The Algorithm Step-by-Step

Algorithm 3 from CS336 Assignment 5: GRPO Training Loop

Here’s the complete GRPO algorithm in pseudocode:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

Algorithm: GRPO Training

Input: policy π_θ, reward function R, training data D, group size G

for step = 1 to n_grpo_steps:

# Step 1: Sample batch of questions

Sample questions {q₁, q₂, ..., qₙ} from D

# Step 2: Generate G responses per question

for each question q:

Sample {o⁽¹⁾, ..., o⁽ᴳ⁾} ~ π_θ(· | q)

Compute rewards {r⁽¹⁾, ..., r⁽ᴳ⁾} using R

# Step 3: Group normalization

μ = mean(r⁽¹⁾, ..., r⁽ᴳ⁾)

σ = std(r⁽¹⁾, ..., r⁽ᴳ⁾)

A⁽ⁱ⁾ = (r⁽ⁱ⁾ - μ) / (σ + ε) for i = 1..G

# Step 4: Store old log-probs for off-policy training

Store log π_θ_old(oₜ | q, o<ₜ) for all tokens

# Step 5: Multiple gradient steps (off-policy)

for epoch = 1 to epochs_per_batch:

Compute policy gradient loss with clipping

Update θ using Adam optimizer

Output: trained policy π_θ

The Group Normalization Formula

The advantage for response i in a group is:

\[A^{(i)} = \frac{r^{(i)} - \mu_G}{\sigma_G + \epsilon}\]where:

- $r^{(i)}$ = reward for response i

- $\mu_G$ = mean reward in the group

- $\sigma_G$ = standard deviation of rewards in the group

- $\epsilon$ = small constant (1e-6) to prevent division by zero

Dr. GRPO variant: Some implementations skip the std normalization:

\[A^{(i)} = r^{(i)} - \mu_G\]This simpler form works well when rewards are binary (0 or 1).

Key Implementation Details

Group-Normalized Rewards

Here’s the core implementation from grpo.py:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

def compute_group_normalized_rewards(

reward_fn,

rollout_responses: list[str],

repeated_ground_truths: list[str],

group_size: int,

advantage_eps: float = 1e-6,

normalize_by_std: bool = True,

) -> tuple[torch.Tensor, torch.Tensor, dict]:

"""

Compute rewards normalized by group statistics.

Args:

reward_fn: Function that scores response against ground truth

rollout_responses: All generated responses (n_questions * group_size)

repeated_ground_truths: Ground truths repeated for each response

group_size: Number of responses per question (G)

normalize_by_std: If True, divide by std (standard GRPO)

If False, only subtract mean (Dr. GRPO)

"""

n_groups = len(rollout_responses) // group_size

# Score all responses

raw_rewards = []

for response, ground_truth in zip(rollout_responses, repeated_ground_truths):

reward_info = reward_fn(response, ground_truth)

raw_rewards.append(reward_info["reward"])

raw_rewards = torch.tensor(raw_rewards, dtype=torch.float32)

# Reshape to (n_groups, group_size) for group-wise operations

rewards_grouped = raw_rewards.view(n_groups, group_size)

# Compute group statistics

group_means = rewards_grouped.mean(dim=1, keepdim=True) # (n_groups, 1)

group_stds = rewards_grouped.std(dim=1, keepdim=True) # (n_groups, 1)

# Compute advantages

if normalize_by_std:

# Standard GRPO: A = (r - mean) / (std + eps)

advantages_grouped = (rewards_grouped - group_means) / (group_stds + advantage_eps)

else:

# Dr. GRPO: A = r - mean

advantages_grouped = rewards_grouped - group_means

# Flatten back to (rollout_batch_size,)

advantages = advantages_grouped.view(-1)

return advantages, raw_rewards, metadata

| Normalization | Formula | When to Use |

|---|---|---|

| Standard GRPO | A = (r - μ) / (σ + ε) | General case, variable rewards |

| Dr. GRPO | A = r - μ | Binary rewards (0/1), simpler |

Three Loss Types

The implementation supports three policy gradient loss types:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

def compute_policy_gradient_loss(

policy_log_probs: torch.Tensor,

loss_type: str, # "no_baseline", "reinforce_with_baseline", "grpo_clip"

raw_rewards: torch.Tensor = None,

advantages: torch.Tensor = None,

old_log_probs: torch.Tensor = None,

cliprange: float = 0.2,

):

if loss_type == "no_baseline":

# Vanilla REINFORCE: -R * log π(a|s)

loss = -raw_rewards * policy_log_probs

elif loss_type == "reinforce_with_baseline":

# REINFORCE with baseline: -A * log π(a|s)

loss = -advantages * policy_log_probs

elif loss_type == "grpo_clip":

# PPO-style clipping for off-policy stability

ratio = torch.exp(policy_log_probs - old_log_probs)

clipped_ratio = torch.clamp(ratio, 1 - cliprange, 1 + cliprange)

# Take minimum (pessimistic bound)

loss = -torch.min(ratio * advantages, clipped_ratio * advantages)

return loss

On-Policy vs Off-Policy: What’s the Difference?

Quick terminology note: In RL for language models, the policy ($\pi$) is the language model being trained. The policy parameters ($\theta$) are the model weights. When we write $\pi_\theta(a \mid s)$, we mean “the probability of generating token $a$ given context $s$, according to the model with weights $\theta$.” The model defines a probability distribution over actions (next tokens) given states (prompt + tokens so far)—that’s exactly what a policy is.

This distinction matters for understanding when to use each loss type:

On-policy: The policy used to generate the data is the same as the policy being updated. Each batch of rollouts is used for exactly one gradient step, then discarded. Simple but wasteful—you throw away expensive samples after one use.

Off-policy: The policy used to generate the data can be different from the policy being updated. This lets you reuse the same batch of rollouts for multiple gradient steps, extracting more learning signal from each expensive generation.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

On-Policy (REINFORCE):

┌──────────────┐ ┌──────────────┐ ┌──────────────┐

│ Generate with│ ──► │ One gradient │ ──► │ Discard │

│ π_θ │ │ step │ │ rollouts │

└──────────────┘ └──────────────┘ └──────────────┘

Off-Policy (GRPO with clipping):

┌──────────────┐ ┌──────────────┐ ┌──────────────┐

│ Generate with│ ──► │ Multiple │ ──► │ Then │

│ π_θ_old │ │ grad steps │ │ discard │

└──────────────┘ └──────────────┘ └──────────────┘

│

Uses ratio ρ = π_θ/π_θ_old

to correct for policy drift

The catch with off-policy: as you update $\theta$, the current policy $\pi_\theta$ drifts away from the old policy $\pi_{\theta_{old}}$ that generated the data. The importance sampling ratio $\rho = \pi_\theta(a \mid s) / \pi_{\theta_{old}}(a \mid s)$ corrects for this, but if $\theta$ changes too much, the correction becomes unreliable. That’s why grpo_clip uses PPO-style clipping—it prevents the ratio from getting too large, keeping updates stable even when reusing rollouts.

Comparison table:

| Loss Type | Formula | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

no_baseline | -R × log π | Simplest | High variance |

reinforce_with_baseline | -A × log π | Lower variance | On-policy only |

grpo_clip | -min(ρA, clip(ρ)A) | Off-policy stable | More complex |

When to use each:

- no_baseline: Debugging, understanding basics

- reinforce_with_baseline: Default choice, good balance

- grpo_clip: When reusing rollouts across multiple gradient steps

Token-Level Loss with Masking

GRPO applies the loss only to response tokens, not the prompt:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Token sequence: │

│ │

│ [What][is][2+3][?][<think>][I][need][to][add][</think>][5][<EOS>] │

│ ├────────────────┤├─────────────────────────────────────────────┤ │

│ PROMPT RESPONSE │

│ mask = 0 mask = 1 │

│ │

│ Loss is computed ONLY over response tokens (mask = 1) │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

The masked_mean function handles this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

def masked_mean(tensor: torch.Tensor, mask: torch.Tensor, dim: int = None):

"""Average only over positions where mask == 1."""

mask_float = mask.float()

masked_tensor = tensor * mask_float

if dim is None:

# Global mean

return masked_tensor.sum() / mask_float.sum().clamp(min=1e-8)

else:

# Mean along dimension

return masked_tensor.sum(dim) / mask_float.sum(dim).clamp(min=1e-8)

Why this matters: Including prompt tokens in the loss would reinforce the model for generating the question—not what we want! We only want to reinforce good answers.

Training Loop and 2-GPU Architecture

This section uses vLLM for fast inference. vLLM is a high-throughput LLM serving engine that uses PagedAttention to efficiently manage GPU memory and continuous batching to maximize throughput. For GRPO, where we need to generate many responses (G per question) quickly, vLLM can be 10-24x faster than standard Hugging Face generate().

Why Separate GPUs?

I used 2× H100 (80GB SXM5) GPUs from Lambda Labs for the GRPO experiments (~6.38 USD/hour). Even with 80GB per GPU, running both vLLM inference and policy training on the same GPU leads to memory contention. GRPO training has two distinct phases with competing memory requirements:

- Rollout generation (inference): Generate G responses per question using vLLM

- Policy training (gradient computation): Update weights using the computed advantages

These phases have different memory patterns:

| Phase | GPU | Memory Breakdown | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rollout (vLLM) | GPU 0 | Model weights (~3GB) + KV cache (~40-60GB at high utilization) | ~65GB |

| Training (Policy) | GPU 1 | Model weights (~3GB) + Optimizer states (~6GB) + Activations (~2-4GB) | ~12GB |

Why not share a single 80GB GPU?

While the training phase only uses ~12GB, combining both workloads is problematic:

- Peak memory overlap: vLLM’s KV cache grows dynamically during generation. If training starts while vLLM is generating long sequences, combined memory can exceed 80GB → OOM.

- Memory fragmentation: vLLM uses PagedAttention which allocates memory in blocks. Frequent allocation/deallocation during training causes fragmentation, reducing effective capacity.

- Throughput loss: Context switching between inference and training modes adds overhead.

The 2-GPU solution is clean: GPU 0 runs vLLM inference exclusively, GPU 1 handles training. After each rollout batch, updated weights are synced from GPU 1 → GPU 0.

GPU Detection and Allocation Logic

The training script detects available GPUs and chooses between two modes:

| Mode | GPUs | Rollout Generation | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-GPU mode | 2+ | vLLM (fast, dedicated GPU) | ~10-24× faster rollouts |

| Single-GPU mode | 1 | HuggingFace generate() | Slower, but works |

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

# From run_grpo.py

import torch

n_gpus = torch.cuda.device_count()

logger.info(f"Detected {n_gpus} GPU(s)")

if n_gpus >= 2:

# 2-GPU mode: vLLM on GPU 0, policy training on GPU 1

use_vllm = True

vllm_device = "cuda:0"

policy_device = "cuda:1"

vllm_instance = init_vllm(

model_id=args.model_name_or_path,

device=vllm_device,

gpu_memory_utilization=0.85,

)

else:

# Single-GPU mode: no vLLM, use HuggingFace generate instead

use_vllm = False

policy_device = "cuda:0"

logger.warning("Only 1 GPU detected. Falling back to HuggingFace generate (slower).")

How does PyTorch know which GPU to use? It doesn’t decide automatically—you specify it in your code. PyTorch requires explicit device placement using .to(device):

1

2

3

4

5

6

# Load policy model explicitly on GPU 1

policy = AutoModelForCausalLM.from_pretrained(model_name)

policy = policy.to("cuda:1") # ← You specify this

# Tensors must also be moved to the same device

input_ids = input_ids.to("cuda:1") # Data must match model's device

If you just call model.cuda() without specifying a device, it defaults to GPU 0. For multi-GPU setups like GRPO, explicit placement (cuda:0, cuda:1) is essential to keep workloads separated.

Why the fallback to use HF generate? vLLM and policy training can’t efficiently share a single GPU—vLLM’s memory management (PagedAttention, continuous batching) conflicts with PyTorch’s training memory patterns. With only 1 GPU, the script disables vLLM entirely and uses HuggingFace’s simpler generate() method, which is slower but avoids memory conflicts.

What is HuggingFace generate()? HuggingFace Transformers is the most popular library for working with pretrained language models. Its model.generate() method is the standard way to produce text from a model—it handles tokenization, sampling strategies (greedy, top-k, top-p), and decoding in a straightforward API. While easy to use and compatible with training (same PyTorch model instance), it processes requests one batch at a time without the advanced optimizations (PagedAttention, continuous batching) that make vLLM fast. For GRPO, this means rollout generation takes longer, but it works reliably on a single GPU.

Decision flowchart:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ GPU Allocation Decision │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ ┌─────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ torch.cuda.device_count() │

│ └───────────┬─────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ┌─────────────────┴─────────────────┐ │

│ ▼ ▼ │

│ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────┐ │

│ │ 1 GPU │ │ 2+ GPUs │ │

│ └──────┬──────┘ └──────┬──────┘ │

│ │ │ │

│ ▼ ▼ │

│ ┌───────────────────────┐ ┌───────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Single-GPU Mode │ │ 2-GPU Mode │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ • Policy: cuda:0 │ │ • vLLM: cuda:0 │ │

│ │ • Rollouts: HF │ │ • Policy: cuda:1 │ │

│ │ generate() (slow) │ │ • Rollouts: vLLM │ │

│ │ • Shared memory │ │ (10-24× faster) │ │

│ └───────────────────────┘ └───────────────────────┘ │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Memory Profiling

The training loop includes memory logging to help diagnose issues:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

def log_gpu_memory(msg: str = "") -> None:

"""Log current GPU memory usage."""

if torch.cuda.is_available():

for i in range(torch.cuda.device_count()):

allocated = torch.cuda.memory_allocated(i) / 1024**3

reserved = torch.cuda.memory_reserved(i) / 1024**3

logger.info(f"GPU {i} {msg}: {allocated:.2f} GB allocated, {reserved:.2f} GB reserved")

Sample output during training:

1

2

3

GPU 0 after vLLM: 62.45 GB allocated, 65.00 GB reserved

GPU 1 after policy: 3.21 GB allocated, 4.50 GB reserved

GPU 1 after optimizer.step(): 9.45 GB allocated, 12.00 GB reserved

What do “allocated” and “reserved” mean?

- Allocated: Memory currently holding tensors (model weights, activations, gradients). This is the memory your code is actively using.

- Reserved: Memory that PyTorch’s CUDA allocator has claimed from the GPU but isn’t currently in use. PyTorch reserves extra memory as a “pool” to avoid expensive allocation calls—when you need new tensors, it pulls from this pool instead of asking the GPU driver.

The gap between reserved and allocated (e.g., 65 - 62.45 = 2.55 GB on GPU 0) is “free” memory within PyTorch’s pool. If you see OOM errors even when allocated seems low, check reserved—fragmentation can cause PyTorch to reserve more than needed.

Memory Optimization Techniques

| Technique | How It Helps | Code Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Gradient checkpointing | Trades compute for memory by recomputing activations during backprop | policy.gradient_checkpointing_enable() |

| Sequence truncation | Limits max context to reduce memory | --max-seq-length-train 512 |

| Cache clearing | Frees unused memory between steps | torch.cuda.empty_cache() |

Explicit del | Removes tensor references immediately | del logits, outputs |

| Smaller micro-batches | Reduces peak memory per step | --gradient-accumulation-steps |

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

# Enable gradient checkpointing to reduce memory usage

if hasattr(policy, 'gradient_checkpointing_enable'):

policy.gradient_checkpointing_enable()

logger.info("Gradient checkpointing enabled")

# In the training loop, free memory aggressively

del log_prob_result, mb_policy_log_probs, loss

gc.collect()

torch.cuda.empty_cache()

The Training Loop

Here’s the step-by-step flow of grpo_train_loop():

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ GRPO Training Iteration │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ 1. Sample batch of prompts from training data │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ "What is 2+3?", "Solve x²=4", ... │ │

│ └───────────────────┬─────────────────────┘ │

│ ▼ │

│ 2. Generate G rollouts per prompt (vLLM or HF generate) │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ 8 responses per question │ │

│ │ Total: n_prompts × 8 responses │ │

│ └───────────────────┬─────────────────────┘ │

│ ▼ │

│ 3. Score responses with reward function (CPU) │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ r1_zero_reward_fn: extracts answer from │ │

│ │ text, compares to ground truth → {0, 1} │ │

│ │ (string processing, no GPU needed) │ │

│ └───────────────────┬─────────────────────┘ │

│ ▼ │

│ 4. Compute group-normalized advantages │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ A = (r - group_mean) / (group_std + ε) │ │

│ └───────────────────┬─────────────────────┘ │

│ ▼ │

│ 5. Forward pass on policy model │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Compute log π_θ(token | context) │ │

│ └───────────────────┬─────────────────────┘ │

│ ▼ │

│ 6. Compute masked policy gradient loss │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Loss = -A × log π (response tokens only)│ │

│ └───────────────────┬─────────────────────┘ │

│ ▼ │

│ 7. Backward pass with gradient accumulation │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ Accumulate gradients over micro-batches │ │

│ └───────────────────┬─────────────────────┘ │

│ ▼ │

│ 8. Optimizer step │

│ ┌─────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ AdamW update, gradient clipping │ │

│ └─────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

GRPO Experiment on Lambda Cloud Setup with 2×H100 (80GB SXM5)

How Two GPUs Work Together in a GRPO Training Setup?

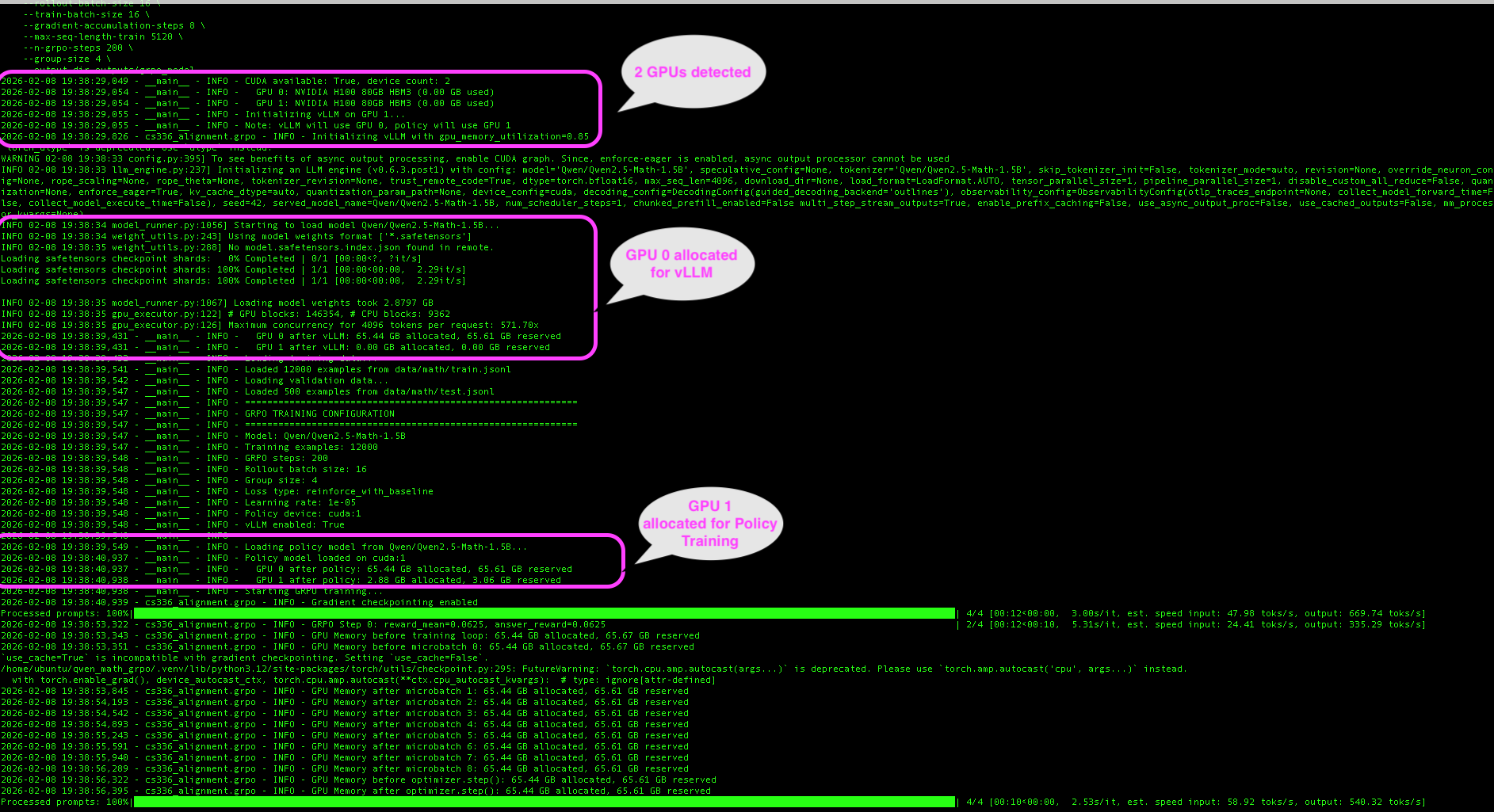

The 2-GPU architecture separates concerns. The screenshot below shows actual training logs from our Lambda Cloud run, with key moments annotated: detecting both H100 GPUs, vLLM claiming GPU 0 for fast rollout generation, and the policy model loading onto GPU 1 for training.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Lambda Cloud 2×H100 Setup │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ GPU 0 (H100 80GB) GPU 1 (H100 80GB) │

│ ┌─────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────┐ │

│ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ vLLM │ │ Policy Model │ │

│ │ (~65 GB) │ │ (~3 GB) │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ - Fast batched │ sync │ - Gradients │ │

│ │ inference │ ◄────────► │ - Optimizer │ │

│ │ - KV cache │ weights │ - Backprop │ │

│ │ - Continuous │ │ │ │

│ │ batching │ │ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │

│ └─────────────────┘ └─────────────────┘ │

│ │

│ Rollout generation Policy training │

│ (inference only) (train mode) │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Understanding the hardware: A Lambda Cloud instance with 2×H100 GPUs also includes a host CPU (typically AMD EPYC or Intel Xeon) that orchestrates all work. The GPUs are accelerators—the CPU runs your Python code, loads data, and dispatches compute-heavy operations to the GPUs.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Lambda Cloud Instance │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ ┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ │

│ │ CPU (Host) │ │

│ │ • Runs Python/PyTorch orchestration code │ │

│ │ • Reward calculation (string parsing, regex) │ │

│ │ • Advantage computation (simple arithmetic) │ │

│ │ • Data loading and preprocessing │ │

│ └──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ │

│ │ │

│ ┌─────────────┴─────────────┐ │

│ ▼ ▼ │

│ ┌─────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────┐ │

│ │ GPU 0 │ │ GPU 1 │ │

│ │ (H100 80GB) │ │ (H100 80GB) │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ vLLM rollouts │ │ Policy training │ │

│ │ (inference) │ │ (forward/back) │ │

│ └─────────────────┘ └─────────────────┘ │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

Where does each step run?

| Step | Location | What Happens |

|---|---|---|

| Rollout generation | GPU 0 | vLLM generates G responses per question |

| Reward calculation | CPU | String parsing—extract answer, compare to ground truth |

| Advantage computation | CPU | Simple arithmetic: (r - μ) / (σ + ε) |

| Policy forward/backward | GPU 1 | Compute log-probs and gradients |

| Optimizer step | GPU 1 | Update weights with AdamW |

| Weight sync | GPU 0 ← GPU 1 | Copy updated weights to vLLM |

Benefits:

- No memory contention between inference and training

- vLLM can use continuous batching without interruption

- Policy model has dedicated memory for optimizer states

- Stable training with predictable memory usage

Step-by-Step Setup

1. Provision Instance

On Lambda Cloud, select an instance with 2+ GPUs:

- 2× A100 (80GB each) - recommended

- 2× H100 (80GB each) - faster, if available

2. SSH and Check GPUs

1

2

3

4

5

6

ssh ubuntu@<your-instance-ip>

# Verify GPUs are visible

nvidia-smi --list-gpus

# Expected: GPU 0: NVIDIA H100 80GB HBM3

# GPU 1: NVIDIA H100 80GB HBM3

3. Install Dependencies

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

# Install uv package manager

curl -LsSf https://astral.sh/uv/install.sh | sh

# Clone and install

git clone https://github.com/bearbearyu1223/qwen_math_grpo.git

cd qwen_math_grpo

uv sync --extra vllm

4. Download Dataset

1

uv run python scripts/download_dataset.py

5. Run Training

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

uv run python scripts/run_grpo.py \

--model-name-or-path Qwen/Qwen2.5-Math-1.5B \

--rollout-batch-size 16 \

--train-batch-size 16 \

--gradient-accumulation-steps 8 \

--max-seq-length-train 1024 \

--n-grpo-steps 200 \

--group-size 8 \

--output-dir outputs/grpo_model

Parameter descriptions:

| Parameter | Value | What It Does |

|---|---|---|

--model-name-or-path | Qwen/Qwen2.5-Math-1.5B | Base model to fine-tune (downloaded from HuggingFace) |

--rollout-batch-size | 16 | Number of questions sampled per GRPO step |

--train-batch-size | 16 | Responses processed per gradient accumulation cycle |

--gradient-accumulation-steps | 8 | Micro-batches accumulated before optimizer update |

--max-seq-length-train | 1024 | Truncates prompt+response to this many tokens. Sequences longer than this limit are cut off. Lower values save GPU memory (activations scale with sequence length²) but may lose reasoning steps. For math problems, 1024 tokens typically covers the question + full solution. |

--n-grpo-steps | 200 | Total training iterations |

--group-size | 8 | Responses generated per question (G in the formula) |

--output-dir | outputs/grpo_model | Where to save checkpoints and logs |

How these numbers relate:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

Questions per step: 16 (rollout-batch-size)

×

Responses per question: 8 (group-size)

═══

Total responses: 128 generated per GRPO step

Training processes: 16 (train-batch-size)

×

Accumulation steps: 8 (gradient-accumulation-steps)

═══

Effective batch: 128 responses per optimizer update

The numbers are chosen so all 128 generated responses are used in exactly one optimizer update. If you reduce rollout-batch-size or group-size, reduce the training side proportionally to match.

6. Download Results

1

2

# From your local machine

scp -r ubuntu@<your-instance-ip>:~/qwen_math_grpo/outputs ./lambda_outputs

Troubleshooting

| Problem | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| CUDA out of memory | Batch size too large | Reduce --rollout-batch-size and --train-batch-size |

| Only 1 GPU detected | vLLM imported before torch | Check import order in code |

| OOM after manual termination of the training process | Zombie processes holding GPU memory | Run nvidia-smi --query-compute-apps=pid --format=csv,noheader \| xargs -I {} kill -9 {} |

| vLLM weight load fails | Wrong vLLM version | Ensure vLLM 0.6.x or 0.7.x (pinned in pyproject.toml) |

Memory-saving parameters:

| Parameter | Description | Reduce If OOM |

|---|---|---|

--rollout-batch-size | Total responses generated per step | Yes |

--train-batch-size | Samples processed per optimizer step | Yes |

--gradient-accumulation-steps | Micro-batch size = train_batch / grad_accum | Increase (smaller micro-batches) |

--max-seq-length-train | Truncate long sequences | Yes |

--group-size | Rollouts per question | Yes |

Interpreting Training Plots

After training, run plot_training.py to visualize metrics:

1

2

3

uv run python scripts/plot_training.py \

--input outputs/grpo_model/training_history.json \

--output training_plot.png

Here’s an example from our training run on Lambda Cloud:

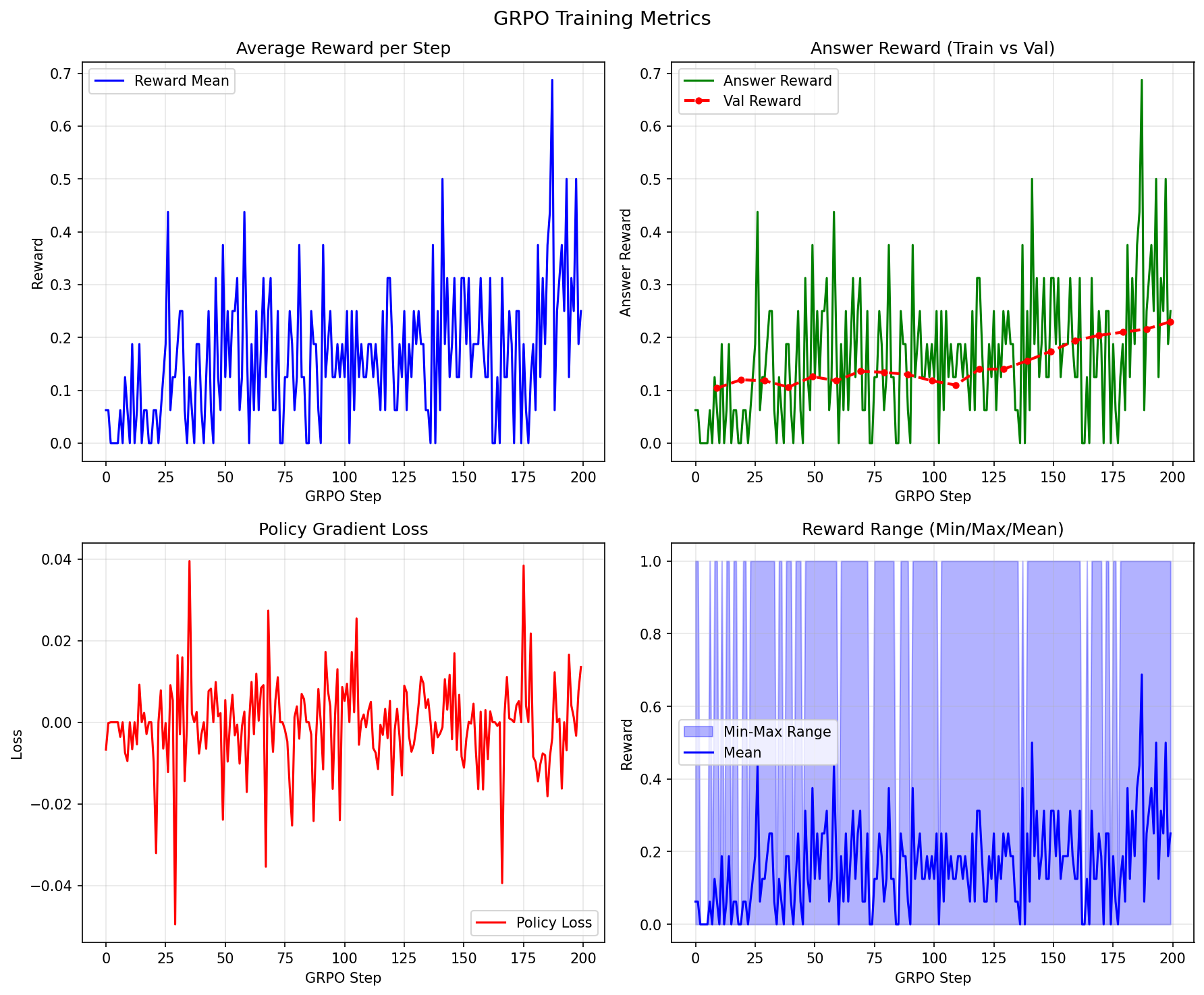

The plot has four panels. Here’s how to interpret each:

Panel 1: Average Reward per Step

What it shows: Mean reward across all responses generated at each GRPO step.

Healthy pattern:

- Gradual upward trend with noise

- Early steps: reward ~0.1-0.2 (model barely better than random)

- Later steps: reward ~0.3-0.5 (model learning)

Problematic patterns:

- Flat line: No learning (check rewards, advantages)

- Wild oscillations: Learning rate too high

- Sudden drops: Policy collapse (reduce learning rate or cliprange)

1

2

3

4

5

6

Healthy: Problematic (flat):

▲ ▲

│ ....●●●● │ ●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●

│ ...●● │

│ ●●● │

└────────────────► step └────────────────────► step

Panel 2: Answer Reward (Train vs Val)

What it shows: Accuracy on training data (green) and validation data (red).

Healthy pattern:

- Both curves trending upward

- Validation slightly below training (normal generalization gap)

- In our run: 6% → 25% accuracy (4× improvement!)

Problematic patterns:

- Train rising, val flat: Overfitting

- Both flat: Not learning

- Val higher than train: Data leakage or evaluation bug

Panel 3: Policy Gradient Loss

What it shows: The loss value from the policy gradient objective.

Healthy pattern:

- Generally decreasing trend with significant noise

- Fluctuations are normal (policy gradient has high variance)

- Should stabilize, not diverge

Problematic patterns:

- NaN values: Numerical instability (reduce learning rate)

- Steadily increasing: Wrong sign or bug

- Extremely low variance: Collapsed policy

Panel 4: Reward Range (Min/Max/Mean)

What it shows: For each training step, this panel plots three values:

- Max reward (top of blue area): The best response in the batch (usually 1 = correct)

- Min reward (bottom of blue area): The worst response in the batch (usually 0 = wrong)

- Mean reward (green line): Average reward across all responses

Why this matters for GRPO:

Remember, GRPO learns by comparing responses within a group. If the model generates 8 responses to a question:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

Diverse (good for learning): Uniform (no learning signal):

┌─────────────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────────────┐

│ Response 1: ✓ (r=1) │ │ Response 1: ✗ (r=0) │

│ Response 2: ✗ (r=0) │ │ Response 2: ✗ (r=0) │

│ Response 3: ✓ (r=1) │ │ Response 3: ✗ (r=0) │

│ Response 4: ✗ (r=0) │ │ Response 4: ✗ (r=0) │

│ ... │ │ ... │

│ min=0, max=1, mean=0.5 │ │ min=0, max=0, mean=0 │

│ │ │ │

│ → Advantages exist! │ │ → All advantages = 0 │

│ → Model can learn │ │ → Nothing to learn from │

└─────────────────────────┘ └─────────────────────────┘

Healthy pattern:

- Blue shaded area spans from 0 to 1 → Some responses correct, some wrong

- Mean line gradually rises → Model getting better over time

- Gap between min and max persists → Model is still exploring, still learning

Problematic patterns:

| Pattern | What You See | What It Means | Fix |

|---|---|---|---|

| Range collapsed to 0 | Blue area stuck at bottom | All responses wrong, no correct examples to reinforce | Problems too hard, or temperature too low (model not exploring) |

| Range collapsed to 1 | Blue area stuck at top | All responses correct, nothing to discourage | Problems too easy, no learning signal |

| Mean not rising | Green line flat | Model not improving despite having diverse responses | Check loss function, learning rate, or reward calculation |

Evaluation Results: Base Model vs GRPO-Trained

After training, we evaluated both the base Qwen2.5-Math-1.5B model and our GRPO-trained model on 500 math problems from the MATH dataset. Here’s the comparison:

| Metric | Base Model | GRPO Model | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correct answers | 69 (13.8%) | 205 (41.0%) | +136 (+197%) |

| Correct format, wrong answer | 122 (24.4%) | 170 (34.0%) | +48 |

| Bad format (couldn’t parse) | 309 (61.8%) | 125 (25.0%) | -184 |

Key improvements:

- 3× accuracy improvement — From 13.8% to 41.0% correct answers

- Format compliance — Bad format responses dropped from 61.8% to 25.0%

- Learning to reason — The model learned to show work and box final answers

Example improvements

Problem 1: Polar coordinates

Convert the point $(0, -3 \sqrt{3}, 3)$ from rectangular to spherical coordinates.

- Base model:

$(6, \frac{2\pi}{3}, \pi)$❌ (wrong angles, no\boxed{}) - GRPO model:

$\boxed{(6, \frac{5\pi}{3}, \frac{2\pi}{3})}$✓ (correct, properly boxed)

Problem 2: Double sum

Compute $\sum_{j = 0}^\infty \sum_{k = 0}^\infty 2^{-3k - j - (k + j)^2}$.

- Base model:

$\frac{4}{3}$❌ (no work shown, unboxed) - GRPO model: Step-by-step derivation →

$\boxed{\frac{4}{3}}$✓

Problem 3: Function evaluation

Given $f(x) = \frac{x^5-1}{3}$, find $f^{-1}(-31/96)$.

- Base model:

$-31/96$❌ (returned input, not inverse) - GRPO model: Derived inverse function →

$\boxed{\frac{1}{2}}$✓

These examples show that GRPO training taught the model to:

- Follow the expected format (

\boxed{}for final answers) - Show intermediate reasoning steps

- Actually compute answers rather than pattern-matching

Summary and Key Takeaways

| Concept | Implementation | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Group normalization | A = (r - μ) / σ computed per question | Natural baseline without value network |

| Response masking | Loss computed on response tokens only | Don’t reinforce the prompt |

| 2-GPU architecture | vLLM on GPU 0, policy on GPU 1 | Avoid memory contention |

| Gradient checkpointing | policy.gradient_checkpointing_enable() | Reduce memory 2-3× |

| Off-policy training | Multiple gradient steps per rollout batch | More efficient data usage |

Quick reference - key hyperparameters:

| Parameter | Default | Effect |

|---|---|---|

group_size (G) | 8 | More diversity → better baseline estimates |

learning_rate | 1e-5 | Higher → faster but unstable |

cliprange (ε) | 0.2 | Higher → more aggressive updates |

gradient_accumulation_steps | 128 | Higher → more stable gradients |

epochs_per_rollout_batch | 1 | Higher → more off-policy (needs clipping) |

Next steps :

- Experiment: Try different group sizes (4, 8, 16) and compare learning curves

- Extend: Add your own reward functions for different tasks

- Scale up: Try larger models (7B) with 4-GPU setups — larger models have more capacity to learn complex reasoning patterns and often start with stronger base capabilities. A 7B model needs ~14GB for weights alone, plus ~28GB for optimizer states, so you’ll need 4 GPUs: 2 for vLLM inference (tensor parallelism) and 2 for policy training

The math may seem daunting, but the core ideas are simple: sample multiple responses, compare them to each other, reinforce the good ones and avoid the bad ones. That’s really all there is to GRPO!

Resources:

- GRPO Training Code (this note’s implementation)

- MATH Dataset on HuggingFace — 12,500 competition math problems

- DeepSeekMath Paper — Original GRPO formulation

- DeepSeek-R1 Paper — GRPO at scale

- Stanford CS336: Language Modeling from Scratch

- Lambda Cloud — GPU instances for training