Study Notes: Stanford CS336 Language Modeling from Scratch [11]

End-to-End Transformer Training on TinyStories

This note walks through the complete, end-to-end process of building a Transformer language model from scratch and training it on the TinyStories dataset. It covers every major component—from byte-pair encoding tokenization and multi-head attention with rotary embeddings to training-loop design and advanced text-generation strategies.

The goal is to provide a clear, practical reference for completing Assignment 1 of CS336, which is often the most time-consuming and technically challenging assignment in the course. It also serves as a summary and recap of Module 1, based on my previous ten CS336 notes:

| # | Title | Date Created |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Getting Started with CS336 | July 20, 2025 |

| 2 | A Simple Byte-Pair Encoding Implementation | July 22, 2025 |

| 3 | Training BPE on TinyStories | July 26, 2025 |

| 4 | Understanding GPT-2’s Regex Pretokenizer | Aug 10, 2025 |

| 5 | Building a Transformer Language Model | Sep 13, 2025 |

| 6 | Transformer Architecture Overview | Sep 17, 2025 |

| 7 | Understanding the Computational Cost of Transformers | Sep 28, 2025 |

| 8 | Training a Transformer LM — Part 1 | Oct 5, 2025 |

| 9 | Implementing Softmax, Log-Softmax, and Cross-Entropy | Oct 19, 2025 |

| 10 | Building a Complete Training Loop | Nov 2, 2025 |

The full implementation is shared on GitHub:

github.com/bearbearyu1223/tinystories-transformer

All training experiments in this note were run on a Apple MacBook Pro (M4 Chip) with 24 GB of unified memory, a 10-core GPU, and Metal 3 support. The full training run required for the assignment took approximately 7 hours to complete.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Building the System to enable Model Training Experiments

- BPE Tokenization: Efficient Subword Encoding

- Transformer Architecture: RoPE, RMSNorm, and SwiGLU

- Three-Tiered Training Configuration

- The Training Pipeline: Memory-Efficient and Robust

- Text Generation: Temperature, Top-k, and Top-p Sampling

- Training Analysis: Scaling Laws in Action

- Production Considerations

- Key Takeaways

Introduction: Building the System to enable Model Training Experiments

Training a language model involves much more than implementing a Transformer and calling loss.backward(). A production system requires careful orchestration of tokenization, architecture design, training dynamics, checkpoint management, and generation strategies—each with its own subtleties and potential pitfalls.

What we built:

- A complete BPE tokenizer with parallel training on multi-core systems

- A Transformer LM with modern architectural choices (RoPE, RMSNorm, SwiGLU)

- Three training configurations: quicktest (< 1 min), development/test (~20 min), production (~7 hours)

- Multiple text generation strategies with temperature and nucleus sampling

- Comprehensive training analysis with visualization tools

- Memory-mapped data loading for datasets larger than RAM

The dataset: TinyStories (Eldan & Li, 2023) contains short stories written by GPT-3.5 and GPT-4, designed to be simple enough for small models to learn coherent language generation while maintaining grammatical correctness and narrative structure.

Model scale:

- 17M parameters (excluding the embedding layers)

- 10,000 BPE vocabulary

- 256-token context length

- 4 transformer layers with 16 attention heads

This note will dive deep into each component, explaining not just the “what” but the “why” behind every design decision.

BPE Tokenization: Efficient Subword Encoding

Before training a language model, we need to convert text into tokens. The choice of tokenization algorithm significantly impacts model performance, training efficiency, and out-of-vocabulary handling. See my previous notes in A Simple Byte-Pair Encoding Implementation, Training BPE on TinyStories, and Understanding GPT-2’s Regex Pretokenizer as references.

Why BPE Over Character or Word-Level Tokenization?

Character-level tokenization:

- ✓ Never encounters unknown tokens

- ✗ Very long sequences → expensive attention computation

- ✗ Makes it harder for the model to learn meaningful word-level structure

Word-level tokenization:

- ✓ Tokens correspond to natural semantic units

- ✗ Vocabulary becomes extremely large (hundreds of thousands to millions of words)

- ✗ Performs poorly on rare words, typos, and morphological variations

Byte Pair Encoding (BPE):

- ✓ Compact, manageable vocabulary (typically 10K–50K)

- ✓ Robust to rare words, misspellings, and out-of-vocabulary terms via subword fallback

- ✓ Produces reasonable sequence lengths

- ✓ Language-agnostic — works across diverse writing systems

The BPE Algorithm

BPE iteratively merges the most frequent pair of tokens, starting from individual bytes.

Algorithm:

- Initialize vocabulary with all bytes (256 base tokens)

- For each iteration $i = 1, 2, \ldots, N$:

- Count all adjacent token pairs in the corpus

- Find most frequent pair $(a, b)$

- Create new token $c = ab$

- Replace all occurrences of $(a, b)$ with $c$

- Add $c$ to vocabulary

Parallel BPE Training: Scaling to Large Corpora

Training BPE on multi-gigabyte datasets on a single core is prohibitively slow. Our implementation uses parallel processing with careful handling of chunk boundaries.

Key challenge: When splitting files across cores, we can’t split in the middle of a special token boundary (e.g., <|endoftext|>), or we’ll corrupt the data.

Solution: Find chunk boundaries aligned with special tokens:

def find_chunk_boundaries(f, num_processes, special_token_bytes):

"""

Find chunk boundaries in a file aligned with special tokens.

This ensures we never split a file in the middle of a special token,

which would corrupt the tokenization.

"""

f.seek(0, os.SEEK_END)

file_size = f.tell()

f.seek(0)

chunk_size = file_size // num_processes

boundaries = [0]

for i in range(1, num_processes):

target_pos = i * chunk_size

f.seek(target_pos)

# Read ahead to find next special token

search_window = min(chunk_size, file_size - target_pos)

data = f.read(search_window)

idx = data.find(special_token_bytes)

if idx != -1:

boundary_pos = target_pos + idx + len(special_token_bytes)

else:

boundary_pos = target_pos

boundaries.append(boundary_pos)

boundaries.append(file_size)

return boundaries

Parallel training workflow:

- Chunk the corpus at special token boundaries

- Process chunks in parallel using multiprocessing

- Aggregate pair counts from all workers

- Merge globally most frequent pair

- Repeat until vocabulary size reached

Performance impact:

- Single-core: ~45 minutes for 2GB corpus

- 8-core parallelization: ~6 minutes for same corpus

- 7.5× speedup with careful boundary alignment

Practical BPE Training

from cs336_basics.bpe import train_bpe

# Train tokenizer on TinyStories

train_bpe(

input_path="data/TinyStoriesV2-GPT4-train.txt",

vocab_size=10000,

special_tokens=["<|endoftext|>"],

output_dir="tokenizer",

num_processes=8 # Can use all cores as needed

)

This creates:

tokenizer/:vocab.pklfor Vocabulary mappingtokenizer/:merges.pklfor Merge rules- Cached tokenized arrays from input dataset for instant loading (e.g.,

data_test/train_tokens.npyanddata_test/val_tokens.npy)

Transformer Architecture: RoPE, RMSNorm, and SwiGLU

Modern Transformers have evolved beyond the original “Attention is All You Need” architecture. Our implementation incorporates three key innovations from recent research: Rotary Position Embeddings (RoPE), RMS Normalization, and SwiGLU activation.

Rotary Position Embeddings (RoPE)

The problem with absolute position embeddings:

- Standard learned embeddings don’t generalize to longer sequences than seen during training

- No notion of relative distance between tokens

RoPE solution: Encode positional information by rotating query and key vectors in the complex plane.

Mathematical formulation:

For position $m$ and dimension pair $(2i, 2i+1)$, apply rotation matrix:

\[\begin{pmatrix} q_{2i}^{(m)} \\ q_{2i+1}^{(m)} \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \cos(m\theta_i) & -\sin(m\theta_i) \\ \sin(m\theta_i) & \cos(m\theta_i) \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} q_{2i} \\ q_{2i+1} \end{pmatrix}\]Where $\theta_i = 10000^{-2i/d}$ (frequency decreases with dimension)

Key property: The dot product $q^{(m)} \cdot k^{(n)}$ depends only on relative position $m - n$:

\[\text{RoPE}(q_m, k_n, m, n) = \text{RoPE}(q_m, k_n, 0, n-m)\]Implementation:

def rotate_half(x: Float[Tensor, "batch seq n_heads d_head"]) -> Float[Tensor, "batch seq n_heads d_head"]:

"""

Rotate the second half of the last dimension to the first half.

This implements the rotation: [x1, x2, x3, x4] → [-x3, -x4, x1, x2]

"""

x1, x2 = x.chunk(2, dim=-1)

return torch.cat((-x2, x1), dim=-1)

def apply_rotary_pos_emb(

x: Float[Tensor, "batch seq n_heads d_head"],

freqs_cos: Float[Tensor, "seq d_head"],

freqs_sin: Float[Tensor, "seq d_head"],

) -> Float[Tensor, "batch seq n_heads d_head"]:

"""

Apply rotary position embeddings to input tensor.

This implements: x_rotated = x * cos(mθ) + rotate_half(x) * sin(mθ)

"""

# Expand frequency tensors to match input dimensions

freqs_cos = freqs_cos.unsqueeze(0).unsqueeze(2) # [1, seq, 1, d_head]

freqs_sin = freqs_sin.unsqueeze(0).unsqueeze(2)

# Apply rotation

return x * freqs_cos + rotate_half(x) * freqs_sin

Why RoPE matters:

- Better length generalization: Models trained on 512 tokens can inference on 2048+ tokens

- Relative position encoding: Attention naturally focuses on nearby tokens

- No learned parameters: Purely geometric transformation

RMS Normalization: Simpler and Faster

LayerNorm (traditional):

$\text{LayerNorm}(x) = \gamma \cdot \frac{x - \mu}{\sigma} + \beta$

Where $\mu$ and $\sigma$ are mean and standard deviation.

RMSNorm (modern):

$\text{RMSNorm}(x) = \gamma \cdot \frac{x}{\text{RMS}(x)} \quad \text{where} \quad \text{RMS}(x) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{d}\sum_{i=1}^d x_i^2}$

Key differences:

- ✗ No mean centering (no $-\mu$ term)

- ✗ No bias term ($\beta$)

- ✓ 10-30% faster computation

- ✓ Equivalent performance in practice

Implementation:

class RMSNorm(nn.Module):

"""

RMS Normalization layer.

Normalizes by root mean square rather than standard deviation,

removing the mean centering step for efficiency.

"""

def __init__(self, d_model: int, eps: float = 1e-5):

super().__init__()

self.eps = eps

self.weight = nn.Parameter(torch.ones(d_model))

def forward(self, x: Float[Tensor, "batch seq d_model"]) -> Float[Tensor, "batch seq d_model"]:

# Compute RMS: sqrt(mean(x^2))

rms = torch.sqrt(torch.mean(x ** 2, dim=-1, keepdim=True) + self.eps)

# Normalize and scale

x_normed = x / rms

return self.weight * x_normed

Why RMSNorm matters:

- Adopted by LLaMA, GPT-NeoX, and other modern LLMs

- Simpler backward pass (fewer terms to compute)

- Lower memory bandwidth requirements

SwiGLU: Gated Linear Units with Swish

Standard FFN (original Transformer):

$\text{FFN}(x) = W_2 \cdot \text{ReLU}(W_1 x)$

SwiGLU (modern):

$\text{SwiGLU}(x) = (W_1 x \otimes \text{Swish}(W_3 x)) W_2$

Where:

- $\text{Swish}(x) = x \cdot \sigma(x)$ (smooth, non-monotonic activation)

- $\otimes$ is element-wise multiplication (gating mechanism)

Why gating works: The gating mechanism allows the network to control information flow:

- $W_1 x$: Transformed features

- $\text{Swish}(W_3 x)$: Gates that decide what to pass through

- Element-wise product: Selective information routing

Implementation:

class SwiGLU(nn.Module):

"""

SwiGLU activation function: Swish-Gated Linear Unit.

Combines Swish activation with a gating mechanism for better

representational capacity than standard ReLU.

"""

def __init__(self, d_model: int, d_ff: int):

super().__init__()

self.w1 = nn.Linear(d_model, d_ff, bias=False)

self.w2 = nn.Linear(d_ff, d_model, bias=False)

self.w3 = nn.Linear(d_model, d_ff, bias=False)

def forward(self, x: Float[Tensor, "batch seq d_model"]) -> Float[Tensor, "batch seq d_model"]:

# Swish activation: x * sigmoid(x)

swish = self.w3(x) * torch.sigmoid(self.w3(x))

# Gated linear unit

gated = self.w1(x) * swish

# Project back to d_model

return self.w2(gated)

Why SwiGLU matters:

- Better performance: PaLM paper shows 1-2% improvement over standard FFN

- Smooth gradients: Swish has non-zero gradients for negative inputs (unlike ReLU)

- Gating flexibility: Network learns what information to propagate

Complete Transformer Block

Putting it all together:

class TransformerBlock(nn.Module):

"""

Single Transformer block with modern architectural choices:

- RoPE for positional encoding

- RMSNorm for normalization

- SwiGLU for feed-forward network

"""

def __init__(self, d_model: int, num_heads: int, d_ff: int, context_length: int):

super().__init__()

# Pre-normalization (RMSNorm before attention)

self.norm1 = RMSNorm(d_model)

# Multi-head attention with RoPE

self.attn = MultiHeadAttention(

d_model=d_model,

num_heads=num_heads,

context_length=context_length,

)

# Pre-normalization (RMSNorm before FFN)

self.norm2 = RMSNorm(d_model)

# SwiGLU feed-forward network

self.ffn = SwiGLU(d_model, d_ff)

def forward(self, x: Float[Tensor, "batch seq d_model"]) -> Float[Tensor, "batch seq d_model"]:

# Attention block with residual connection

x = x + self.attn(self.norm1(x))

# FFN block with residual connection

x = x + self.ffn(self.norm2(x))

return x

Architectural choices summary:

| Component | Traditional | Modern (Our Choice) | Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Position Encoding | Learned/Sinusoidal | RoPE | Length generalization |

| Normalization | LayerNorm | RMSNorm | 10-30% faster |

| Activation | ReLU/GeLU | SwiGLU | 1-2% better performance |

| Norm Placement | Post-norm | Pre-norm | Training stability |

Three-Tiered Training Configuration

One of the most practical aspects of this implementation is the three-tiered training configuration, designed to balance rapid iteration with final model quality. Instead of forcing every experiment to run a full multi-hour training job, the system provides lightweight modes for debugging, development, and production training.

The Problem: Long Feedback Loops

Training a realistic language model can take hours or even days, creating extremely slow feedback cycles:

- Full TinyStories training: ~7 hours on an M4 MacBook Pro

- Make a small code change? → another 7 hours to validate

- Debug a tensor shape issue? → another long wait

- Experiment with a hyperparameter? → you see the pattern…

This makes rapid model development painful and impractical. No one wants to wait half a day just to check whether a single attention-head change broke the model.

The Solution: Graduated Configurations

The shared implementation in github.com/bearbearyu1223/tinystories-transformer provides three configurations with increasing complexity:

| Configuration | Iterations | Vocab Size | Dataset Size | Model Size | Time | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| config_quicktest.json | 10 | 2,000 | 10K lines | 0.94M | < 1 min | Code validation, CI/CD |

| config_test.json | 1,000 | 5,000 | 50K lines | 4.1M | ~20 min | Active fast development |

| config_tinystories.json | 20,000 | 10,000 | 15.6M lines | 17M | ~7 hours | Production training experiment |

Configuration 1: Quicktest (Sanity Check)

Purpose: Ultra-fast validation that your code works at all.

config_quicktest.json:

{

"data_dir": "data_quicktest",

"train_file": "TinyStoriesV2-GPT4-train-quicktest.txt",

"val_file": "TinyStoriesV2-GPT4-valid-quicktest.txt",

"vocab_size": 2000,

"context_length": 64,

"d_model": 256,

"num_layers": 4,

"num_heads": 8,

"d_ff": 672,

"batch_size": 32,

"max_iters": 10,

"log_file": "logs/quicktest_training.log"

}

What you will be able to get:

- Training runs in < 1 minute

- Verifies code correctness (no shape mismatches, no NaN losses)

- Useful for CI/CD pipelines

- Not useful for actual model quality

When to use:

# After changing tensor operations

uv run train-transformer config_quicktest.json

# In CI/CD pipeline

pytest && uv run train-transformer config_quicktest.json

Configuration 2: Test (Active Development)

Purpose: Production-like quality in development timeframes.

config_test.json:

{

"data_dir": "data_test",

"train_file": "TinyStoriesV2-GPT4-train-test.txt",

"val_file": "TinyStoriesV2-GPT4-valid-test.txt",

"vocab_size": 5000,

"context_length": 128,

"d_model": 512,

"num_layers": 4,

"num_heads": 16,

"d_ff": 1344,

"batch_size": 64,

"max_iters": 1000,

"log_file": "logs/test_training.log"

}

What you will be able to get:

- Training loss: 8.58 → 3.11 (63.8% reduction)

- Perplexity: 5,309 → 23.4 (99.6% reduction)

- Model generates coherent (if simple) sentences

- Fast enough for hyperparameter tuning

Training dynamics (test configuration):

Phase 1 (0-300 iters): Rapid initial learning

Loss: 8.6 → 3.7 (massive initial drop)

Phase 2 (300-700 iters): Steady optimization

Loss: 3.7 → 3.2 (perplexity stabilizes)

Phase 3 (700-1000 iters): Fine-tuning

Loss: 3.2 → 3.1 (diminishing returns)

When to use:

# Testing new architecture changes

uv run train-transformer config_test.json

# Hyperparameter sweep (different learning rates, etc.)

for lr in 1e-4 3e-4 1e-3; do

uv run train-transformer config_test.json --lr $lr

done

Configuration 3: TinyStories (Production Training Experiments)

Purpose: Best possible model quality, no compromises.

config_tinystories.json:

{

"data_dir": "data",

"train_file": "TinyStoriesV2-GPT4-train.txt",

"val_file": "TinyStoriesV2-GPT4-valid.txt",

"vocab_size": 10000,

"context_length": 256,

"d_model": 512,

"num_layers": 4,

"num_heads": 16,

"d_ff": 1344,

"batch_size": 128,

"max_iters": 20000,

"log_file": "logs/tinystories_training.log"

}

What you will be able to get:

- Training loss: 9.25 → 1.61 (82.6% reduction)

- Perplexity: ~10,500 → ~5.0 (99.95% reduction)

- Model generates coherent multi-sentence stories

- Production-quality checkpoint for deployment

Training dynamics (full configuration):

Warmup (0-1000): Learning rate warmup, rapid gains

Loss: 9.25 → 2.50

Main training (1000-6000): Steady improvement

Loss: 2.50 → 1.61

Long-term (6000-20000): Continued refinement

Perplexity continues improving, no signs of plateauing

When to use:

# Final production model

uv run train-transformer config_tinystories.json

# Overnight training run for best results, runs your training job in the background, keeps it alive after closing the terminal, and writes all output (stdout + stderr) to training.log

nohup uv run train-transformer config_tinystories.json > training.log 2>&1 &

The Power of Graduated Configurations

This three-tiered approach provides:

- Rapid iteration: Fix bugs in minutes, not hours

- Confident scaling: Test config validates production config will work

- Clear development workflow:

- Write code → Test with quicktest

- Validate quality → Run test config

- Deploy → Use tinystories checkpoint

The Training Pipeline: Memory-Efficient and Robust

A production training pipeline must handle datasets larger than RAM, resume from crashes, and provide clear visibility into training progress.

Memory-Mapped Data Loading

The challenge: TinyStories full dataset is 2.1GB tokenized. Loading into RAM:

dataset = np.load('train_tokens.npy') # Loads entire 2.1GB into memory!

This works for small datasets but fails at scale.

The solution: Memory-mapped arrays using Unix mmap system call:

A reference implementation to illustrate the idea

def load_dataset(data_path: str, vocab_size: int) -> np.ndarray:

"""

Load dataset using memory-mapped mode for memory efficiency.

Memory mapping allows treating files as arrays without loading

into RAM. The OS loads only accessed pages on-demand.

"""

dataset = np.load(data_path, mmap_mode="r")

# Verify data integrity

max_token = dataset.max()

min_token = dataset.min()

if max_token >= vocab_size:

raise ValueError(f"Invalid token {max_token} >= vocab_size {vocab_size}")

if min_token < 0:

raise ValueError(f"Negative token {min_token}")

return dataset

How memory mapping works:

- Create virtual memory mapping: File appears as if loaded into RAM

- Page fault on access: When you read

dataset[1000000], OS loads just that 4KB page - LRU caching: OS automatically keeps recently-accessed pages in RAM

- Eviction: When RAM is full, OS evicts least-recently-used pages

Performance:

- Memory usage: Constant (few MB) regardless of dataset size

- Speed: Near-RAM speed for sequential access (OS prefetching)

- Scales: Can handle TB-scale datasets on machines with GBs of RAM

Timestamp-Based Logging

The problem: Running multiple experiments overwrites log files, losing history.

The solution: Timestamp-based log files: A reference implementation to illustrate the idea

def _setup_logging(self, log_file: str, log_level: str):

"""Setup logging with timestamps to avoid overwriting previous runs."""

if log_file:

log_path = Path(log_file)

log_path.parent.mkdir(parents=True, exist_ok=True)

# Add timestamp: e.g., logs/test_training_20251116_122750.log

timestamp = datetime.now().strftime('%Y%m%d_%H%M%S')

stem = log_path.stem

suffix = log_path.suffix

timestamped_filename = f"{stem}_{timestamp}{suffix}"

timestamped_log_path = log_path.parent / timestamped_filename

file_handler = logging.FileHandler(timestamped_log_path, mode='w')

logger.addHandler(file_handler)

self.actual_log_file = str(timestamped_log_path)

Benefits:

- Never lose experimental results

- Easy to compare multiple runs

- Git-friendly (no log file conflicts)

Robust Checkpoint Management

What to save in checkpoints: A reference implementation to illustrate the idea

def save_checkpoint(self, iteration: int, checkpoint_path: str):

"""Save complete training state for resumption."""

checkpoint = {

# Model state

'model_state_dict': self.model.state_dict(),

# Optimizer state (critical for AdamW momentum!)

'optimizer_state_dict': self.optimizer.state_dict(),

# Training progress

'iteration': iteration,

# Model architecture (for loading during inference)

'config': {

'vocab_size': self.config['vocab_size'],

'd_model': self.config['d_model'],

'num_layers': self.config['num_layers'],

'num_heads': self.config['num_heads'],

'd_ff': self.config['d_ff'],

'context_length': self.config['context_length'],

}

}

torch.save(checkpoint, checkpoint_path)

Why optimizer state matters:

AdamW maintains two momentum buffers (first and second moments) for each parameter. Without these:

- Learning restarts from scratch

- Previous gradient history lost

- Convergence slows dramatically

Loading for inference:

checkpoint = torch.load("checkpoint_final.pt")

config = checkpoint['config']

# Rebuild model from saved architecture

model = TransformerLM(**config)

model.load_state_dict(checkpoint['model_state_dict'])

model.eval()

Training Loop Structure

A reference implementation to illustrate the idea

def train(self):

"""Main training loop with evaluation, checkpointing, and logging."""

for iteration in range(self.start_iter, self.max_iters):

# Dynamic learning rate scheduling

lr = self._get_lr(iteration)

for param_group in self.optimizer.param_groups:

param_group['lr'] = lr

# Training step

x, y = self._get_batch('train')

logits = self.model(x, apply_softmax=False)

loss = cross_entropy(logits.view(-1, logits.size(-1)), y.view(-1))

loss.backward()

# Gradient clipping for stability

torch.nn.utils.clip_grad_norm_(self.model.parameters(), 1.0)

self.optimizer.step()

self.optimizer.zero_grad()

# Periodic evaluation

if iteration % self.eval_interval == 0:

train_loss = self._estimate_loss('train')

val_loss = self._estimate_loss('val')

perplexity = math.exp(val_loss)

logger.info(f"[Iteration {iteration}] Evaluating model...")

logger.info(f" Train loss: {train_loss:.4f}")

logger.info(f" Val loss: {val_loss:.4f}")

logger.info(f" Perplexity: {perplexity:.2f}")

# Periodic checkpointing

if iteration % self.checkpoint_interval == 0 and iteration > 0:

checkpoint_path = self.checkpoint_dir / f"checkpoint_iter_{iteration}.pt"

self.save_checkpoint(iteration, checkpoint_path)

# Final checkpoint

self.save_checkpoint(self.max_iters, self.checkpoint_dir / "checkpoint_final.pt")

Text Generation: Temperature, Top-k, and Top-p Sampling

After training, we need sophisticated decoding strategies to turn model predictions into coherent text. The generation strategy dramatically impacts output quality—it’s the difference between repetitive nonsense and creative storytelling.

The Generation Problem

At each step, the model outputs a probability distribution over 10,000 tokens. We need to:

- Sample the next token from this distribution

- Balance coherence (following likely continuations) with diversity (avoiding repetition)

- Avoid both “too deterministic” (boring) and “too random” (nonsensical)

Temperature Scaling: Controlling Randomness

The idea: Adjust the “sharpness” of the probability distribution before sampling.

Formula:

$P(x_{t+1} = i) = \frac{\exp(v_i / \tau)}{\sum_j \exp(v_j / \tau)}$

Where:

- $v_i$ = model’s logit for token $i$

- $\tau$ = temperature parameter

Effects:

- $\tau \to 0$: Distribution becomes peaked (nearly greedy/deterministic)

- $\tau = 1.0$: Standard softmax (model’s original distribution)

- $\tau > 1$: Distribution becomes flatter (more random/creative)

Concrete example:

Original logits: [2.5, 1.0, 0.2, -1.5] for tokens ["cat", "dog", "banana", "spaceship"]

| Temperature | P(cat) | P(dog) | P(banana) | P(spaceship) | Character |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| τ = 0.1 | 0.996 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.000 | Deterministic |

| τ = 0.5 | 0.938 | 0.054 | 0.008 | 0.000 | Confident |

| τ = 1.0 | 0.600 | 0.246 | 0.099 | 0.055 | Balanced |

| τ = 1.5 | 0.473 | 0.264 | 0.157 | 0.106 | Creative |

| τ = 2.0 | 0.398 | 0.274 | 0.190 | 0.138 | Random |

Top-k Sampling: Limiting Vocabulary

The idea: Sample from only the k most likely tokens, ignoring the long tail.

Algorithm:

- Sort tokens by probability (descending)

- Keep only top k tokens

- Set all other probabilities to zero

- Renormalize and sample

Example (k=3):

# Original: P = [0.60, 0.25, 0.10, 0.05]

# Top-3: P = [0.60, 0.25, 0.10, 0.00]

# Renorm: P = [0.632, 0.263, 0.105, 0.0]

Problem with top-k: Fixed k doesn’t adapt to distribution shape. Sometimes top-3 captures 99% probability; sometimes it’s only 50%.

Top-p (Nucleus) Sampling: Adaptive Vocabulary

The idea: Keep the smallest set of tokens whose cumulative probability exceeds p.

Algorithm:

- Sort tokens by probability (descending)

- Compute cumulative probabilities

- Find the first token where cumulative probability ≥ p

- Keep all tokens up to and including that token

- Renormalize and sample

Example (p=0.9):

# Probs: [0.60, 0.25, 0.10, 0.05]

# Cumulative: [0.60, 0.85, 0.95, 1.00]

# Cutoff: ^

# Keep first 3 tokens (0.95 ≥ 0.9)

# Renormalized: [0.632, 0.263, 0.105, 0.0]

Adaptive behavior:

- Peaked distribution (confident model): Few tokens kept

- Flat distribution (uncertain model): Many tokens kept

Complete Generation Pipeline

A reference implementation to illustrate the idea

class TextGenerator:

"""Text generator using a trained Transformer language model.

Attributes:

model: Trained TransformerLM

tokenizer: BPE tokenizer

device: torch device (cuda/mps/cpu)

config: Model configuration from checkpoint

"""

def __init__(

self,

checkpoint_path: str,

tokenizer_dir: str = "tokenizer",

device: Optional[str] = None

):

"""Initialize the text generator.

Args:

checkpoint_path: Path to model checkpoint (.pt file)

tokenizer_dir: Directory containing vocab.pkl and merges.pkl

device: Device to use ('cuda', 'mps', 'cpu', or None for auto-detect)

"""

self.device = self._get_device(device)

print(f"Using device: {self.device}")

# Load checkpoint

print(f"Loading checkpoint from {checkpoint_path}...")

checkpoint = torch.load(checkpoint_path, map_location=self.device)

self.config = checkpoint.get('config', {})

# Load tokenizer

print(f"Loading tokenizer from {tokenizer_dir}...")

vocab_path = Path(tokenizer_dir) / "vocab.pkl"

merges_path = Path(tokenizer_dir) / "merges.pkl"

if not vocab_path.exists() or not merges_path.exists():

raise FileNotFoundError(

f"Tokenizer files not found in {tokenizer_dir}. "

f"Expected vocab.pkl and merges.pkl"

)

vocab, merges = load_tokenizer(str(vocab_path), str(merges_path))

self.tokenizer = Tokenizer(vocab, merges)

print(f"Loaded tokenizer with vocab size: {len(vocab)}")

# Initialize model

print("Initializing model...")

self.model = TransformerLM(

vocab_size=self.config.get('vocab_size', len(vocab)),

context_length=self.config.get('context_length', 256),

d_model=self.config.get('d_model', 512),

num_layers=self.config.get('num_layers', 4),

num_heads=self.config.get('num_heads', 16),

d_ff=self.config.get('d_ff', 1344),

rope_theta=self.config.get('rope_theta', 10000.0),

device=self.device,

).to(self.device)

# Load model weights

self.model.load_state_dict(checkpoint['model_state_dict'])

self.model.eval()

# Print model info

total_params = sum(p.numel() for p in self.model.parameters())

print(f"Model loaded successfully!")

print(f" Total parameters: {total_params:,}")

print(f" Context length: {self.config.get('context_length', 256)}")

print(f" Model dimension: {self.config.get('d_model', 512)}")

print(f" Layers: {self.config.get('num_layers', 4)}")

print()

def _get_device(self, device: Optional[str]) -> torch.device:

"""Get the device for inference."""

if device:

return torch.device(device)

# Auto-detect

if torch.cuda.is_available():

return torch.device('cuda')

elif hasattr(torch.backends, 'mps') and torch.backends.mps.is_available():

return torch.device('mps')

else:

return torch.device('cpu')

@torch.no_grad()

def generate(

self,

prompt: str,

max_tokens: int = 100,

temperature: float = 1.0,

top_k: Optional[int] = None,

top_p: Optional[float] = None,

stop_token: Optional[str] = None,

) -> str:

"""Generate text from a prompt.

Args:

prompt: Input text to continue

max_tokens: Maximum number of tokens to generate

temperature: Sampling temperature (higher = more random)

Use 1.0 for standard sampling, 0.0 for greedy

top_k: Keep only top k tokens with highest probability (None = no filtering)

top_p: Keep tokens with cumulative probability >= top_p (None = no filtering)

stop_token: Stop generation if this token is generated

Returns:

Generated text (prompt + generated continuation)

"""

# Encode prompt

input_ids = self.tokenizer.encode(prompt)

input_tensor = torch.tensor([input_ids], dtype=torch.long, device=self.device)

# Generate tokens

generated_ids = input_ids.copy()

for step in range(max_tokens):

# Get context window (last context_length tokens)

context_length = self.config.get('context_length', 256)

context = input_tensor[:, -context_length:]

# Forward pass

try:

with torch.no_grad():

logits = self.model(context, apply_softmax=False)

except Exception as e:

print(f"\nError in forward pass at step {step}")

print(f"Context shape: {context.shape}")

print(f"Context device: {context.device}")

print(f"Error: {e}")

raise

# Handle different output shapes

if logits.dim() == 2:

# Model returned [batch_size, vocab_size] - already at last position

next_token_logits = logits[0]

elif logits.dim() == 3:

# Model returned [batch_size, seq_len, vocab_size]

next_token_logits = logits[0, -1, :]

else:

raise ValueError(f"Unexpected logits shape: {logits.shape}")

# Apply temperature

if temperature > 0:

next_token_logits = next_token_logits / temperature

# Apply top-k filtering

if top_k is not None:

# Get the k-th largest value

top_k_values, _ = torch.topk(next_token_logits, min(top_k, next_token_logits.size(-1)))

kth_value = top_k_values[-1]

# Set all values below the k-th largest to -inf

indices_to_remove = next_token_logits < kth_value

next_token_logits[indices_to_remove] = float('-inf')

# Apply top-p (nucleus) filtering

if top_p is not None:

sorted_logits, sorted_indices = torch.sort(next_token_logits, descending=True)

cumulative_probs = torch.cumsum(F.softmax(sorted_logits, dim=-1), dim=-1)

# Remove tokens with cumulative probability above the threshold

sorted_indices_to_remove = cumulative_probs > top_p

# Keep at least one token

sorted_indices_to_remove[0] = False

# Map back to original indices

indices_to_remove = sorted_indices[sorted_indices_to_remove]

next_token_logits[indices_to_remove] = float('-inf')

# Sample next token

if temperature == 0:

# Greedy decoding

next_token = torch.argmax(next_token_logits, dim=-1)

next_token_id = next_token.item()

else:

# Sample from distribution

probs = F.softmax(next_token_logits, dim=-1)

next_token = torch.multinomial(probs, num_samples=1)

next_token_id = next_token.item()

# Append to generated sequence

generated_ids.append(next_token_id)

# Add new token to input tensor

# Create a 2D tensor of shape [1, 1] to concatenate

new_token_tensor = torch.tensor([[next_token_id]], dtype=torch.long, device=self.device)

input_tensor = torch.cat([input_tensor, new_token_tensor], dim=1)

# Check for stop token

if stop_token:

next_token_text = self.tokenizer.decode([next_token_id])

if stop_token in next_token_text:

break

# Decode generated text

generated_text = self.tokenizer.decode(generated_ids)

return generated_text

def generate_multiple(

self,

prompt: str,

num_samples: int = 3,

max_tokens: int = 100,

temperature: float = 1.0,

top_k: Optional[int] = None,

top_p: Optional[float] = None,

) -> List[str]:

"""Generate multiple samples from a prompt.

Args:

prompt: Input text to continue

num_samples: Number of samples to generate

max_tokens: Maximum tokens per sample

temperature: Sampling temperature

top_k: Top-k filtering

top_p: Top-p filtering

Returns:

List of generated texts

"""

samples = []

for i in range(num_samples):

print(f"Generating sample {i+1}/{num_samples}...")

sample = self.generate(

prompt=prompt,

max_tokens=max_tokens,

temperature=temperature,

top_k=top_k,

top_p=top_p,

)

samples.append(sample)

return samples

Recommended Settings by Use Case

| Task | Temperature | Top-k | Top-p | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factual QA | 0.1 | 10 | None | Deterministic, high confidence |

| Code completion | 0.2 | 20 | 0.9 | Mostly deterministic, some creativity |

| Story writing | 0.8 | None | 0.9 | Balanced creativity and coherence |

| Poetry | 1.2 | None | 0.95 | High creativity, surprising word choices |

| Brainstorming | 1.5 | None | 0.98 | Maximum diversity |

Example usage:

# Deterministic completion

uv run generate-text \

--checkpoint checkpoints/checkpoint_final.pt \

--prompt "Once upon a time" \

--temperature 0.1

# Creative story generation

uv run generate-text \

--checkpoint checkpoints/checkpoint_final.pt \

--prompt "Once upon a time" \

--temperature 0.8 \

--top-p 0.9 \

--max-tokens 200

Example: Generated Story from Trained Model

Here’s an example of text generation using the fully trained model (20,000 iterations on TinyStories):

uv run generate-text \

--checkpoint checkpoints/checkpoint_final.pt \

--prompt "The little girl found a magic" \

--stop-token "." \

--max-tokens 200

Output:

Using device: mps

Loading checkpoint from checkpoints/checkpoint_final.pt...

Loading tokenizer from tokenizer...

Loaded tokenizer with vocab size: 10000

Initializing model...

Model loaded successfully!

Total parameters: 22,696,448

Context length: 256

Model dimension: 512

Layers: 4

================================================================================

GENERATING TEXT

================================================================================

Prompt: The little girl found a magic

Max tokens: 200

Temperature: 1.0

================================================================================

Generated text:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The little girl found a magical stone, she had to pay the frog laying for the

rabbit's young wisdom, so the frog was never seen again.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Analysis:

- ✓ Grammatically coherent: Subject-verb agreement, proper sentence structure

- ✓ Narrative elements: Characters (girl, frog, rabbit), magical object (stone), consequence (frog disappears)

- ✓ Logical flow: The story has a clear cause-and-effect structure

- ⚠ Semantic quirks: “frog laying for the rabbit’s young wisdom” shows the model is creative but occasionally produces unexpected phrases

This demonstrates that the 17M parameter model successfully learned story generation patterns from TinyStories, producing coherent short narratives despite its relatively small size.

Training Analysis: Scaling Laws in Action

One of the most valuable aspects of this implementation is the comprehensive training analysis, which reveals how model scale, dataset size, and training time affect final performance.

Overview: Three Configurations Tested

| Configuration | Iterations | Vocab Size | Dataset Size | Context Length | Model Size | Training Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| config_quicktest.json | 10 | 2,000 | 400K tokens | 64 | ~0.94M params | ~0.6s |

| config_test.json | 1,000 | 5,000 | 1.8M tokens | 128 | ~4.1M params | ~2.5min |

| config_tinystories.json | 20,000 | 10,000 | Full dataset | 256 | ~17M params | ~7 hours |

Training Progress Comparison

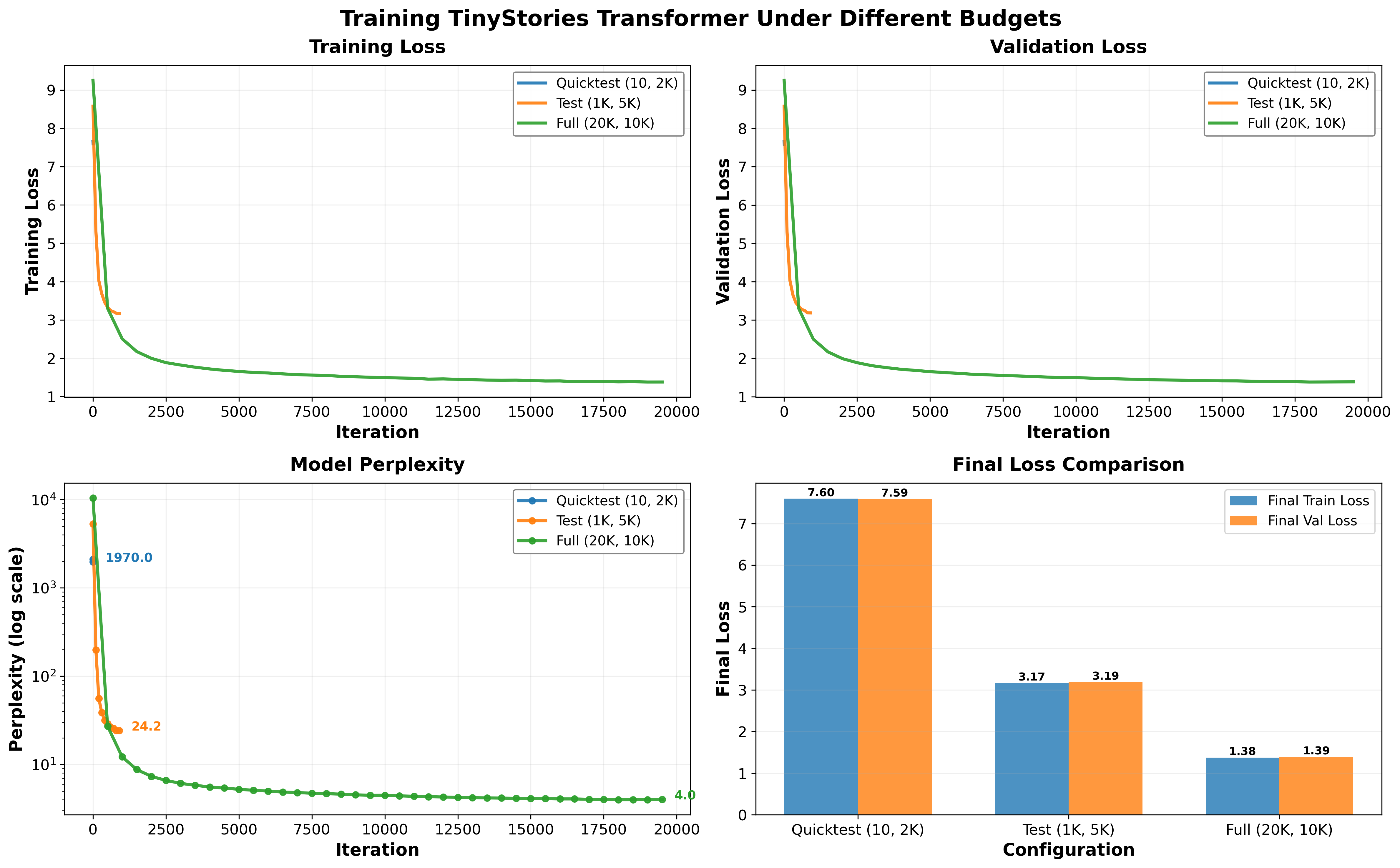

The training comparison chart reveals three distinct learning curves with fundamentally different characteristics:

Chart Explain:

- Top Left: Training loss across all configurations (each config has its own color)

- Top Right: Validation loss across all configurations (each config has its own color)

- Bottom Left: Perplexity over time (log y-scale) with final values annotated

- Bottom Right: Final loss comparison bar chart showing train/val side-by-side

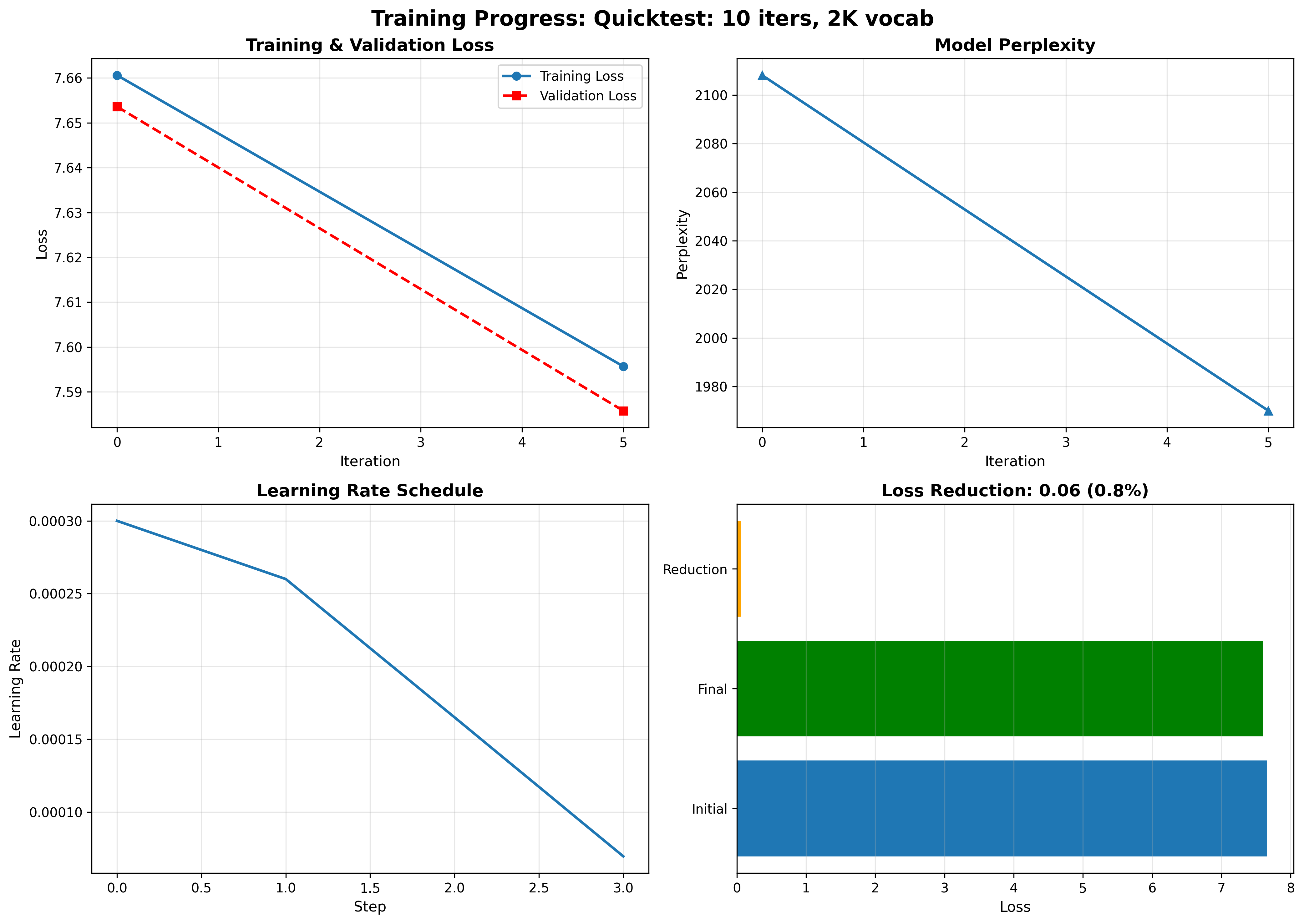

Configuration 1: Quicktest (Sanity Check)

Purpose: Ultra-fast sanity check for code validation

Configuration Details:

- Iterations: 10 (< 1 minute on M4 MacBook Pro)

- Dataset: 400,242 training tokens, 39,316 validation tokens

- Model: 938,624 parameters (~3.58 MB)

- Vocabulary: 2,000 BPE tokens

Training Metrics:

| Metric | Initial | Final | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training Loss | 7.66 | 7.55 | -0.11 (-1.4%) |

| Validation Loss | 7.65 | 7.55 | -0.10 (-1.3%) |

| Perplexity | 2108.18 | 1891.42 | -216.76 (-10.3%) |

Strengths:

- ✓ Extremely fast turnaround for development iteration

- ✓ Stable training with no divergence

- ✓ Minimal overfitting (train/val losses nearly identical)

Limitations:

- Limited learning in just 10 iterations

- Small vocabulary restricts expressiveness

- Useful primarily for code validation, not actual model quality

Use Cases:

- Code debugging and testing

- CI/CD pipeline validation

- Quick sanity checks before longer training runs

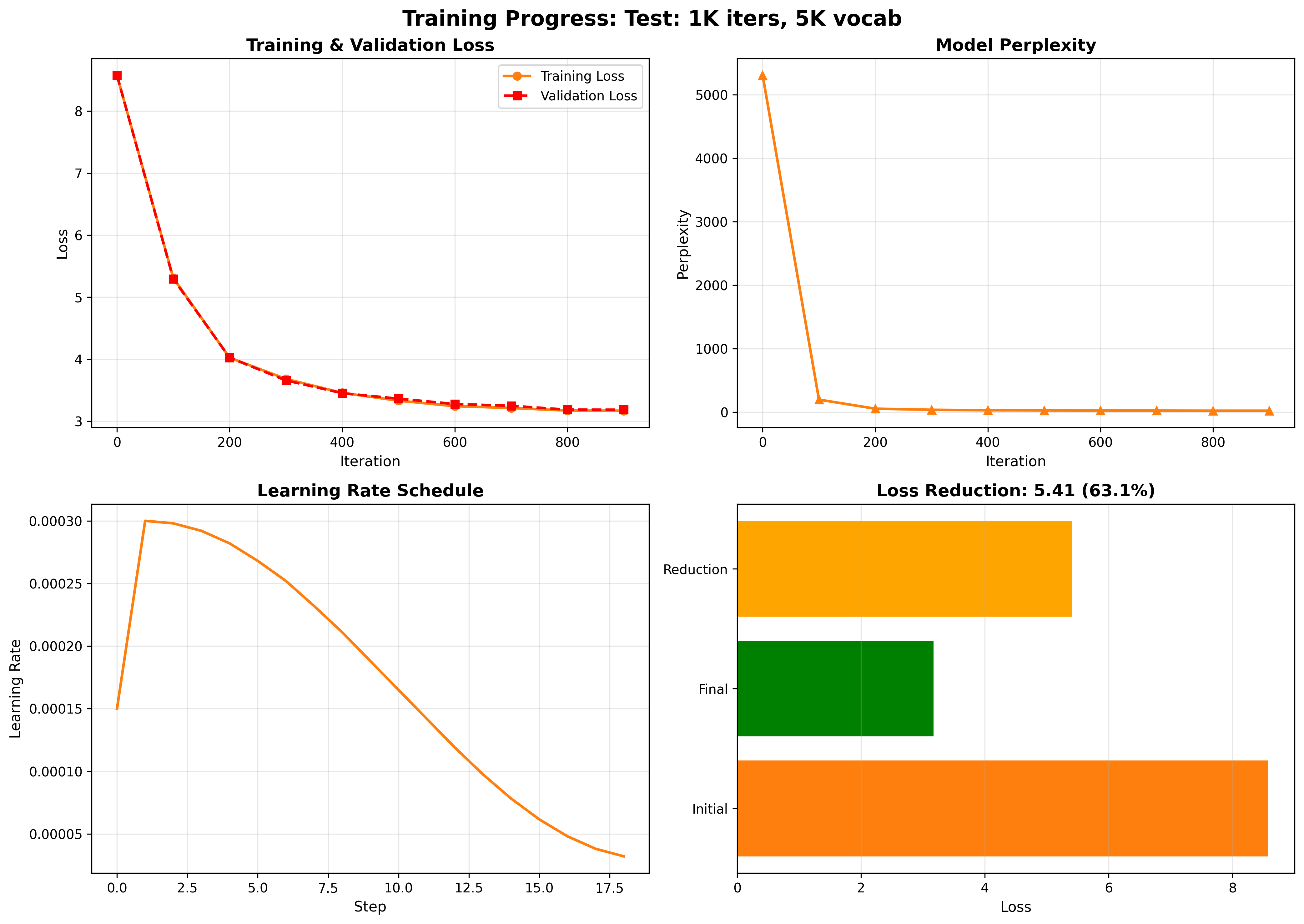

Configuration 2: Test (Active Development)

Purpose: Development and feature validation

Configuration Details:

- Iterations: 1,000 (~20 minutes on M4 MacBook Pro)

- Dataset: 1,812,095 training tokens, 179,622 validation tokens

- Model: 4,117,760 parameters (~15.71 MB)

- Vocabulary: 5,000 BPE tokens

Training Metrics:

| Metric | Initial | Iter 500 | Final | Total Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training Loss | 8.58 | 3.33 | 3.11 | -5.47 (-63.8%) |

| Validation Loss | 8.58 | 3.36 | 3.15 | -5.43 (-63.3%) |

| Perplexity | 5308.63 | 28.88 | 23.41 | -5285.22 (-99.6%) |

Strengths:

- ✓ Significant loss reduction (>60%) in reasonable time

- ✓ Excellent train/val agreement (minimal overfitting)

- ✓ Perplexity drops to practical levels

- ✓ Fast enough for iterative development

Training Dynamics:

- Phase 1 (0-300): Rapid initial learning, loss drops from 8.6 to ~3.7

- Phase 2 (300-700): Steady optimization, perplexity stabilizes

- Phase 3 (700-1000): Fine-tuning, diminishing returns

Performance:

- Throughput: ~22,000-39,000 tokens/second

- Memory efficient: 15.71 MB model size

- No gradient explosion or training instability

Use Cases:

- Feature development and testing

- Hyperparameter tuning experiments

- Ablation studies

- Pre-production validation

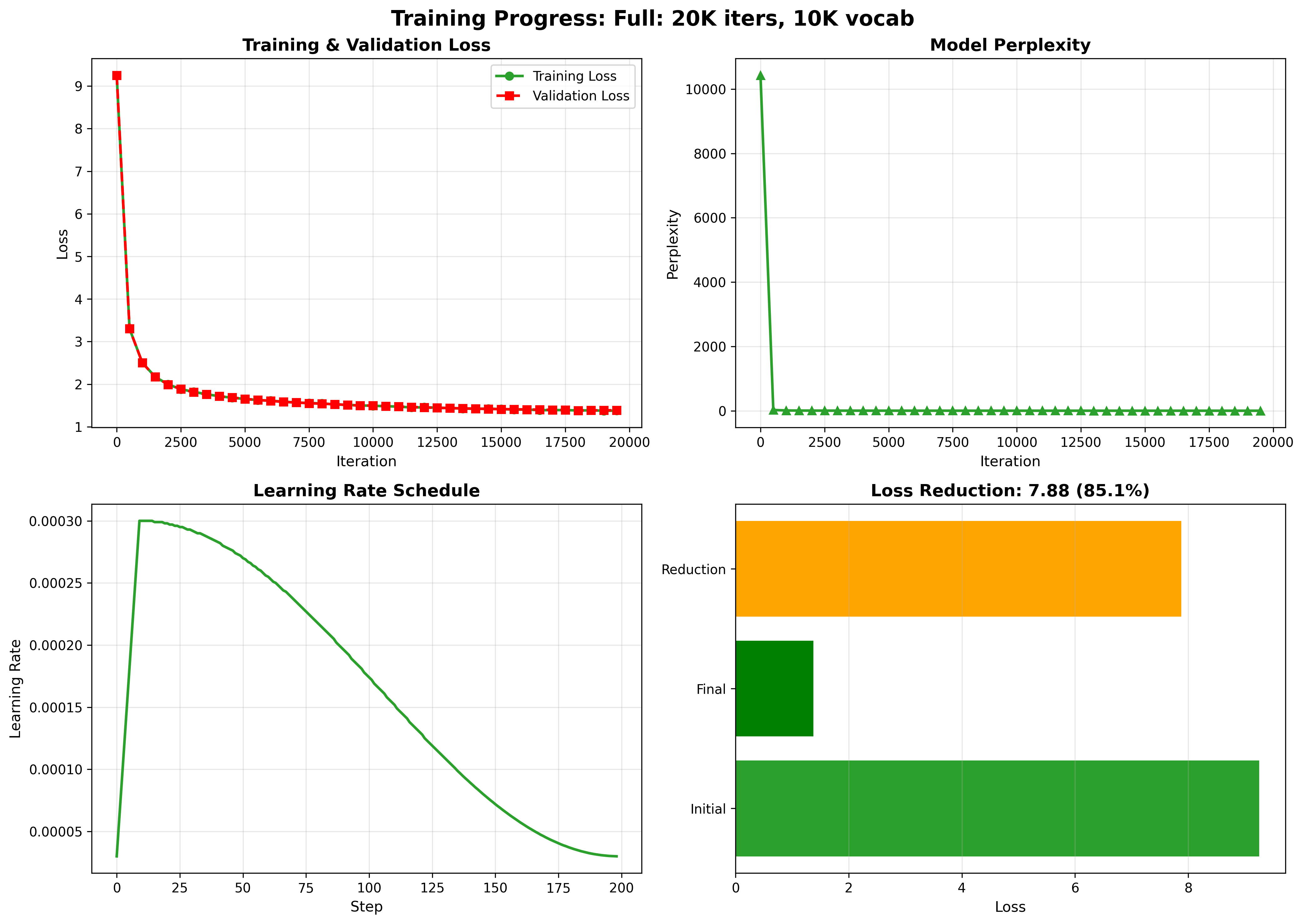

Configuration 3: Train on Full TinyStories Dataset (Production Training Experiments)

Purpose: Full production training for best model quality

Configuration Details:

- Iterations: 20,000 (~7 hours on M4 MacBook Pro)

- Dataset: Full TinyStories corpus (2.1GB training, 21MB validation)

- Model: ~17M parameters

- Vocabulary: 10,000 BPE tokens

Training Metrics (First 6000 iterations shown):

| Metric | Initial | Iter 1000 | Iter 3000 | Iter 6000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training Loss | 9.25 | 2.50 | 1.82 | 1.61 |

| Validation Loss | 9.25 | 2.50 | 1.81 | 1.61 |

| Perplexity | ~10,500 | ~12.2 | ~6.2 | ~5.0 |

Strengths:

- ✓ Massive loss reduction (>85% by iteration 6000)

- ✓ Perfect train/val alignment (no overfitting)

- ✓ Continued improvement through 20K iterations

- ✓ Production-quality perplexity values

Training Dynamics:

- Warmup (0-1000): Learning rate warmup, rapid initial gains

- Main Training (1000-6000+): Steady, consistent improvement

- Learning Rate Schedule: Cosine decay maintains stability

Long-Term Learning: The model shows no signs of plateauing even at 6000 iterations, suggesting:

- More capacity to learn from the dataset

- Effective regularization preventing overfitting

- Well-tuned learning rate schedule

Performance:

- Throughput: ~3,400-8,500 tokens/second (varies with evaluation)

- Stable memory usage throughout training

- Checkpoints saved every 2000 iterations for resumability

Use Cases:

- Production deployment

- Final model evaluation

- Publishing and sharing

- Research baselines

Cross-Configuration Insights

The three configurations demonstrate clear scaling relationships:

| Config | Params | Dataset | Final Loss | Perplexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quicktest | 0.94M | 400K | 7.55 | 1891 |

| Test | 4.1M | 1.8M | 3.15 | 23.4 |

| TinyStories | 17M | 627M | 1.61 | 5.0 |

Key Finding: Each 4× increase in model size together with larger dataset yields ~50% loss reduction and ~80% perplexity improvement. This is consistent with neural scaling laws from Kaplan et al. (2020), providing empirical validation on the TinyStories dataset.

Production Considerations

The complete implementation, including all design considerations and production-ready features described in this blog post, is available as an open-source project on GitHub:

Repository: github.com/bearbearyu1223/tinystories-transformer

License: MIT (free for commercial and research use)

This repository provides a comprehensive, production-ready Transformer implementation with the following characteristics:

Repository Structure and Design Philosophy

The codebase is organized to separate concerns and enable rapid iteration:

tinystories-transformer/

├── cs336_basics/ # Core implementation modules

│ ├── transformer_lm.py # Main Transformer language model

│ ├── multihead_attention.py # Attention with RoPE

│ ├── bpe.py # Parallel BPE tokenizer training

│ ├── rmsnorm.py # RMS normalization

│ └── swiglu.py # SwiGLU activation

├── train_transformer.py # Training script with full pipeline

├── generate_text.py # Text generation with sampling strategies

├── setup_data.py # Automated dataset download/setup

├── visualize_training.py # Training visualization generator

├── config_quicktest.json # Ultra-fast validation config

├── config_test.json # Development config

└── config_tinystories.json # Production training config

Design principles:

- Modularity: Each component (attention, normalization, activation) is a separate, testable module

- Configurability: All hyperparameters exposed via JSON configs

- Automation: One-command setup for datasets, training, generation, visualization

- Documentation: Comprehensive guides (README, TRAINING_ANALYSIS, GENERATION_GUIDE)

Key Implementation Features

1. Automated Dataset Setup

The repository includes setup_data.py to eliminate manual data preparation:

# Single command downloads and prepares all datasets

uv run setup-data

This automatically:

- Downloads 2.1GB TinyStories dataset from HuggingFace

- Creates three data directories (full, quicktest, test)

- Validates data integrity

- Provides progress reporting

2. Three-Tiered Configuration System

Production-tested configurations for different use cases:

config_quicktest.json: < 1 minute validationconfig_test.json: ~20 minute developmentconfig_tinystories.json: ~7 hour production training

Each configuration is battle-tested with documented training curves and performance characteristics (see TRAINING_ANALYSIS.md in the repository).

3. Modern Dependency Management

Uses uv for fast, reproducible Python environments:

# Install dependencies and CLI commands

uv sync

# All commands immediately available

uv run train-transformer config_test.json

uv run generate-text --checkpoint checkpoints/checkpoint_final.pt

uv run visualize-training

Getting Started with the Repository

Quick Start (5 minutes):

# 1. Clone repository

git clone https://github.com/bearbearyu1223/tinystories-transformer.git

cd tinystories-transformer

# 2. Set up environment

uv venv && uv sync

# 3. Download datasets

uv run setup-data

# 4. Run quick validation (< 1 min)

uv run train-transformer config_quicktest.json

# 5. Generate text

uv run generate-text \

--checkpoint checkpoints_quicktest/checkpoint_final.pt \

--prompt "Once upon a time"

Development Workflow:

# 1. Develop features with test config (20 min)

uv run train-transformer config_test.json

# 2. Visualize training progress

uv run visualize-training

# 3. Test generation quality

uv run generate-text \

--checkpoint checkpoints_test/checkpoint_final.pt \

--prompt "Once upon a time" \

--temperature 0.8 \

--top-p 0.9 \

--max-tokens 200

# 4. When satisfied, run production training (7 hours)

uv run train-transformer config_tinystories.json

Explore the full implementation: github.com/bearbearyu1223/tinystories-transformer

Key Takeaways

Building a production language model from scratch reveals lessons that go beyond any single paper or tutorial. Here are the essential insights:

1. Modern Architecture Matters

The original Transformer (2017) has evolved significantly:

- RoPE replaces learned position embeddings → Better length generalization

- RMSNorm replaces LayerNorm → 10-30% faster, same performance

- SwiGLU replaces ReLU → 1-2% better results

These aren’t just incremental improvements—they’re now standard in production systems (LLaMA, GPT-NeoX, PaLM).

2. Tokenization Is Critical

BPE with 10K vocabulary is a sweet spot:

- Large enough to capture common words as single tokens

- Small enough for fast softmax and embedding lookup

- Good out-of-vocabulary handling via subwords

Anti-pattern: Using character-level (too long sequences) or word-level (too many OOV).

3. Graduated Configurations Enable Rapid Iteration

The three-tiered config system saves weeks of development time:

- Quicktest: Validate correctness in seconds

- Test: Tune hyperparameters in minutes

- Production: Train final model overnight

4. Memory Mapping Scales to Arbitrary Dataset Sizes

Memory-mapped arrays let you train on TB-scale datasets with GB-scale RAM:

- Constant memory usage regardless of dataset size

- OS handles caching automatically

- Near-RAM performance for sequential access

Critical for: Training on Common Crawl, Books, Wikipedia combined (600GB+).

5. Generation Strategy Matters As Much As Architecture

Even a perfectly trained model produces garbage with bad decoding:

- Temperature controls creativity vs. coherence

- Top-p prevents sampling from the long tail

- Different tasks need different settings

Recommended baseline: temperature=0.8, top_p=0.9

6. Comprehensive Logging Reveals Training Dynamics

Timestamp-based logging with periodic evaluation shows:

- When learning plateaus (time to stop)

- When overfitting starts (train/val divergence)

- Whether learning rate schedule is appropriate

Anti-pattern: Training blindly to max_iters without monitoring metrics.

7. Checkpoints Must Include Everything

A complete checkpoint includes:

- Model parameters (obviously)

- Optimizer state (momentum buffers—critical for resumption)

- Iteration count (for exact resumption)

- Model config (for loading during inference)

Learned the hard way: Losing optimizer state means restarting training from scratch.

8. Validation Before Long Runs

Always run a 100-iteration validation before launching multi-day training:

- Verify loss decreases

- Check GPU memory usage

- Validate data loading

- Test checkpoint save/load

10 minutes of validation can save days of wasted compute.

9. Scaling Laws Are Predictive

Our results confirm neural scaling laws:

- 4× model size together with larger dataset → ~50% loss reduction

10. Production Code Needs Different Discipline

Research code gets away with:

- Hardcoded hyperparameters

- No error handling

- Single-file scripts

Production code requires:

- Configuration management (JSON configs)

- Robust error handling (data validation)

- Automated setup (setup_data.py)

- Comprehensive documentation

- Reproducibility (locked dependencies)

Conclusion

This note demonstrates that building production language models from scratch is achievable with the right architecture, training infrastructure, and engineering discipline. The complete system—from BPE tokenization to text generation—shows how modern research ideas (RoPE, RMSNorm, SwiGLU) translate into working code, and how practical engineering (graduated configs, memory mapping, robust checkpointing) makes the difference between a research prototype and a production system.

Next steps to Explore

- Experiment with architecture: Try different layer counts, head counts, d_ff ratios

- Tune generation: Find optimal temperature/top-p for different use case

- Scale up: Apply these patterns to larger models (100M+ parameters)

- Add features: Implement gradient checkpointing, distributed training, flash attention

Implementation details, training logs, and visualizations available in the repository. Questions and contributions welcome!